http://www.leftyparent.com/blog/2011/10/15/napoleon-prussia-the-u-s-education-system/

October 15th, 2011 at 15:00

I love the narratives of human history, especially when compelling threads can be drawn out (hopefully real and not just imagined) connecting events, choices and consequences over the scope of centuries. I am particularly drawn to contemplating how a particular event, and how people chose to react to that event, can impact events centuries later. For example, the cynical machismo of Western leaders (along with their countries’ intellectuals and artists) driving choices that lead to World War I. One could argue that this power struggle at the expense of cultural suicide destroyed the “immune system” of Western culture and led to the “cancers” that followed: economic depression; the growth of totalitarian states driven by fascism, Nazism, and Stalinism; and the wars (hot and cold) and other holocausts that they perpetrated on their fellow humans throughout the century.

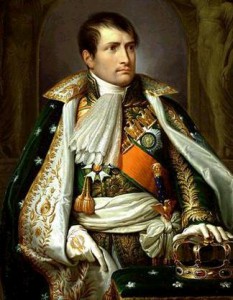

In a less apocalyptic vein, I have been contemplating these past few days another historical narrative thread that links Napoleon Bonaparte and particularly his victory over the Prussians at the 1806 battle of Jena with the development of the public school system in America and the continuing educational controversies, dysfunction and dilemma that we have in that area today. I was inspired by a comment made by a reader of my blog piece “Schooled to Accept Economic Inequity”, regarding my reference to the Prussian influence in the development of the U.S. public school system.

I first read about that Prussian connection in John Taylor Gatto‘s book, The Underground History of American Education, a book which has shaken and reshaped my whole conception of education as much as Riane Eisler‘s book, The Chalice and the Blade, has reshaped my understanding of human history and the challenge of that history today. It is Gatto’s insight which I then try to put into Eisler’s framework of a continuing cultural thread of patriarchal top-down control.

From Chapter Seven of Gatto’s book, focused on the U.S. education system’s Prussian connection…

In a less apocalyptic vein, I have been contemplating these past few days another historical narrative thread that links Napoleon Bonaparte and particularly his victory over the Prussians at the 1806 battle of Jena with the development of the public school system in America and the continuing educational controversies, dysfunction and dilemma that we have in that area today. I was inspired by a comment made by a reader of my blog piece “Schooled to Accept Economic Inequity”, regarding my reference to the Prussian influence in the development of the U.S. public school system.

I first read about that Prussian connection in John Taylor Gatto‘s book, The Underground History of American Education, a book which has shaken and reshaped my whole conception of education as much as Riane Eisler‘s book, The Chalice and the Blade, has reshaped my understanding of human history and the challenge of that history today. It is Gatto’s insight which I then try to put into Eisler’s framework of a continuing cultural thread of patriarchal top-down control.

From Chapter Seven of Gatto’s book, focused on the U.S. education system’s Prussian connection…

The particular utopia American believers chose to bring to the schoolhouse was Prussian. The seed that became American schooling, twentieth-century style, was planted in 1806 when Napoleon’s amateur soldiers bested the professional soldiers of Prussia at the battle of Jena. When your business is renting soldiers and employing diplomatic extortion under threat of your soldiery, losing a battle like that is pretty serious. Something had to be done. (Gatto page 131)

You may think it a stretch, but I think it is at least a good story with truth to it. A narrative thread of how the patriarchal control paradigm perpetuates itself within a larger context of human civilization’s transition from hierarchies of power and control towards a circle of equals. So here goes…

Napoleon: The Quintessential Modern Man

Given my interest since my youth in military history and board game simulations of that history, I have always had great interest in the military campaigns of this noted historical figure. But it wasn’t until I read the two part biography of Napoleon by Robert Asprey, The Rise Of Napoleon Bonaparte and The Reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, that I got a more holistic view of this amazing person and the things he accomplished amidst his own ego, imperial power, and war that he was at the center of.

As good as he was as a military strategist and tactician, he was equally good or better as an administrator and nation builder. He developed the French civil code of law, now known as “The Napoleonic Code”, that, according to Wikipedia, “forbade privileges based on birth, allowed freedom of religion, and specified that government jobs go to the most qualified”. Unlike other conquering generals, he developed the infrastructure of and encouraged the national aspirations of the territories seized by his armies. There were some 360 political divisions in Central Europe when his armies first march from France. By the time his efforts were finally defeated and he was exiled, there were just 36, many asserting their nationalism for the first time.

Historian Jacques Barzun in his book From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, quotes French writer and social critic Stendhal, who had served in his army in the retreat from Russia, and wrote a biography of Napoleon in 1816, confessing in the introduction…

Napoleon: The Quintessential Modern Man

Given my interest since my youth in military history and board game simulations of that history, I have always had great interest in the military campaigns of this noted historical figure. But it wasn’t until I read the two part biography of Napoleon by Robert Asprey, The Rise Of Napoleon Bonaparte and The Reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, that I got a more holistic view of this amazing person and the things he accomplished amidst his own ego, imperial power, and war that he was at the center of.

As good as he was as a military strategist and tactician, he was equally good or better as an administrator and nation builder. He developed the French civil code of law, now known as “The Napoleonic Code”, that, according to Wikipedia, “forbade privileges based on birth, allowed freedom of religion, and specified that government jobs go to the most qualified”. Unlike other conquering generals, he developed the infrastructure of and encouraged the national aspirations of the territories seized by his armies. There were some 360 political divisions in Central Europe when his armies first march from France. By the time his efforts were finally defeated and he was exiled, there were just 36, many asserting their nationalism for the first time.

Historian Jacques Barzun in his book From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, quotes French writer and social critic Stendhal, who had served in his army in the retreat from Russia, and wrote a biography of Napoleon in 1816, confessing in the introduction…

I feel a kind of religious sentiment as I dare to write the first sentence of a history of Napoleon. It deals with the greatest man since Caesar. His superiority lay entirely in his way of finding new ideas with incredible speed, of judging them with complete rationality, and of carrying them out with a willpower that never had an equal. (Barzun page 483)

Stendhal was a fellow Frenchman, but even Napoleon’s enemies, in the end, had great respect for him. Here’s Beethoven in 1820…

Napoleon understood the spirit of the times. As a German I have been his greatest enemy. But actual conditions have reconciled me to him. He understood art and science and despised ignorance. (Barzun page 483)

Barzun’s own thoughts on Napoleon’s legacy…

It was the will to take heroic risks that settled the place of Napoleon in the imagination of artists and peoples… It completed the extinction of feudal vestiges and his cavalier handling of kings and princes sustained his character of champion of the people. The world at large seems still to side with him, not Wellington, since everywhere Waterloo has become a synonym for defeat, not victory. (Barzun page 485)

All this background on Napoleon is important to this story, because he represented the spirit of the emerging nationalism of the 19th century. And though he crowned himself Emperor of France and wielded incredible powers, he was viewed by many, including some of the most intelligent thinkers in Europe at the time, as the model of the “enlightened despot” and state architect of a better society. This is particularly important, because Napoleon became the personification of the modern myth that best practices, implemented in an enlightened top-down control model, could change the face of human society for the better.

Case and point to buying into that mythology was Frederick Hegel and the emerging Prussian state.

Prussia & the Legacy of the 1806 Battle of Jena

A generation earlier a previous “enlightened despot”, Frederick the Great, had led a Prussian army and conquered and unified a number of the independent German states under the flag of a greater Prussia. After the French revolution deposed the French King and set up the first republic on the continent of Europe, that greater Prussia, led by Frederick’s successor, had joined with the other major monarchies of Europe to wage war on the new republican menace that France posed to the political status quo of Europe. In 1806 an army of the republic of France, led by Napoleon, marched into Prussia in a preemptive strike to protect the fledgling nation from one of its powerful monarchist adversaries.

The armies met outside the town of Jena in the German state of Saxony. The brilliant battlefield improvisations of Napoleon along with the superior training and morale of the French citizen soldiers contributed to a decisive defeat and destruction of Prussia’s highly trained professional mercenary army, and led to the subjugation of Prussia under French control for the next six years. It was not lost on the losers that their professional army was defeated by a force made up of inspired volunteers. The defeat shook the entire Prussian aristocracy and they committed themselves to literally retool their entire country to ensure that it would never happen again.

Two key players in that retooling effort were influential German philosopher Johann Fichte and his star protégé, the young Frederick Hegel. Here’s Gatto on Fichte’s framing of his country’s humiliating loss and what needed to be done in terms of lessons learned…

Case and point to buying into that mythology was Frederick Hegel and the emerging Prussian state.

Prussia & the Legacy of the 1806 Battle of Jena

A generation earlier a previous “enlightened despot”, Frederick the Great, had led a Prussian army and conquered and unified a number of the independent German states under the flag of a greater Prussia. After the French revolution deposed the French King and set up the first republic on the continent of Europe, that greater Prussia, led by Frederick’s successor, had joined with the other major monarchies of Europe to wage war on the new republican menace that France posed to the political status quo of Europe. In 1806 an army of the republic of France, led by Napoleon, marched into Prussia in a preemptive strike to protect the fledgling nation from one of its powerful monarchist adversaries.

The armies met outside the town of Jena in the German state of Saxony. The brilliant battlefield improvisations of Napoleon along with the superior training and morale of the French citizen soldiers contributed to a decisive defeat and destruction of Prussia’s highly trained professional mercenary army, and led to the subjugation of Prussia under French control for the next six years. It was not lost on the losers that their professional army was defeated by a force made up of inspired volunteers. The defeat shook the entire Prussian aristocracy and they committed themselves to literally retool their entire country to ensure that it would never happen again.

Two key players in that retooling effort were influential German philosopher Johann Fichte and his star protégé, the young Frederick Hegel. Here’s Gatto on Fichte’s framing of his country’s humiliating loss and what needed to be done in terms of lessons learned…

The most important immediate reaction to Jena was an immortal speech, the “Addresses to the German Nation” by the philosopher Fichte – one of the influential documents of modern history leading directly to the first workable compulsion schools in the West… In no uncertain terms Fichte told Prussia the party was over. Children would have to be disciplined through a new form of universal conditioning. They could no longer be trusted to their parents. Fichte said that, “Education should provide the means to destroy free will”. Look what Napoleon had done by banishing sentiment in the interests of nationalism. Through forced schooling, everyone would learn that “work makes free”, and working for the State, even laying down one’s life to its commands, was the greatest freedom of all. Here in the genius of semantic redefinition lay the power to cloud men’s minds, a power later packaged and sold by public relations pioneer Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee in the seedtime of American forced schooling… (Gatto page 131)

Think about even today, how many of us in 21st century America still make the argument, that when it comes to the education of our youth, parents and the young students themselves cannot be trusted to do the right thing guiding their own education for the betterment of our society.

According to Barzun, the young Hegel had an epiphany on the path forward for Prussia and Western culture generally, in the lessons learned from Napoleon and the debacle at Jena…

According to Barzun, the young Hegel had an epiphany on the path forward for Prussia and Western culture generally, in the lessons learned from Napoleon and the debacle at Jena…

Periodically a mere man comes to look superhuman: he is able to change the face of society when all previous efforts have met unshakable resistance. Hegel was well placed for making this portrait from life: he was in a cellar in Jena while Napoleon was fighting to victory above ground… For the majority of thinkers and artists he [Napoleon] remained the genius in whom they recognized and celebrated not themselves as individuals, but their drive to achievement… Here was no ordinary conqueror for booty, but a man who fashioned a new Europe. The areas of influence, the efficiency of his administration, his code of laws, his active role in art and science, his lapidary judgments of men and society, even his ambition, ruthless but lofty, bespoke the heroic character.(Barzun page 484)

Prussia Develops the 19th Century’s State-of-the-Art Education System

Hegel became the leading figure of a budding young German intelligentsia who championed the role of the enlightened despot, intelligently and deftly directing the resources of a large modern state. According to Gatto and seconded by Barzun, that vision inspired the Prussian education revolution that followed, which included a complete transformation, instituting the first mandatory universal schooling in the Western world. It was a three-tiered system built around the privilege of the Prussian aristocracy but also leveraging the modern concept of meritocracy, at least to the degree that it supported the aristocratic hierarchy. The jewel in the crown was the new University of Berlin, perhaps the first “modern” university in the world.

The top tier of their equivalent of the modern “K-12” system (remember… the Germans invented the “K” part) were private schools reserved for the children of the aristocracy, Prussia’s “one percent”…

Hegel became the leading figure of a budding young German intelligentsia who championed the role of the enlightened despot, intelligently and deftly directing the resources of a large modern state. According to Gatto and seconded by Barzun, that vision inspired the Prussian education revolution that followed, which included a complete transformation, instituting the first mandatory universal schooling in the Western world. It was a three-tiered system built around the privilege of the Prussian aristocracy but also leveraging the modern concept of meritocracy, at least to the degree that it supported the aristocratic hierarchy. The jewel in the crown was the new University of Berlin, perhaps the first “modern” university in the world.

The top tier of their equivalent of the modern “K-12” system (remember… the Germans invented the “K” part) were private schools reserved for the children of the aristocracy, Prussia’s “one percent”…

At the top, one-half of 1 percent of the students attended Akadamiesschulen, where, as future policy makers, they learned to think strategically, contextually, in wholes; they learned complex processes, and useful knowledge, studied history, wrote copiously, argued often, read deeply, and mastered tasks of command. (Gatto page 137)

The remaining two tiers were government run, and all about ranking and sorting the rest of Prussia’s youth so they could best play the needed roles in the nation’s apparatus. Tier two was for the “best of the rest”…

The next level, Realsschulen, was intended mostly as a manufactory for the professional proletariat of engineers, architects, doctors, lawyers, career civil servants, and such other assistants as policy thinkers at times would require. From 5 to 7.5 percent of all students attended these “real schools”, learning in a superficial fashion how to think in context, but mostly learning how to manage materials, men, and situations – to be problem solvers. This group would also staff the various policing functions of the state, bringing order to the domain. (Gatto page 137)

I keep thinking of that great Russian word, “apparatchik”, for people who hold key positions withing the bureaucratic or political “apparatus” that runs an organization or country.

And last (and least in terms of position in the societal hierarchy)…

And last (and least in terms of position in the societal hierarchy)…

A group of between 92 and 94 percent of the population attended “people’s schools” [Volksschulen] where they learned obedience, cooperation and correct attitudes, along with rudiments of literacy and official state myths of history. (Gatto page 137)

In Gatto’s provocative summary, these Prussian educational visionaries…

Held a clear idea of what centralized schooling should deliver: 1) Obedient soldiers to the army; 2) Obedient workers for mines, factories, and farms; 3) Well-subordinated civil servants, trained in their function; 4) Well-subordinated clerks for industry; 5) Citizens who thought alike on most issues; 6) National uniformity in thought, word and deed. (Gatto page 131)

The most academically inclined of the privileged aristocrats and the best of the commoners attended the flagship of the new system, the University of Berlin, where Hegel was the anchor of the philosophy department.

James Billington captures the revolutionary spirit of this institution of higher learning in his book, Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith…

James Billington captures the revolutionary spirit of this institution of higher learning in his book, Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith…

The new university at Berlin was the intellectual heart of the Prussian revival after Prussia’s humiliation by Napoleon. Hegel was central to its intellectual life not only as professor of philosophy from 1818 until his death in 1831, but for many years thereafter. Founded in 1809, the University of Berlin was in many ways the first modern university – urban, research-oriented, state-supported, free from traditional religious controls. Berlin stood at at the apex of the entire state educational system of reform Prussia. Deliberately located in the capital rather than in the traditional sleepy provincial town, the University of Berlin breathed an atmosphere of political expectation and intellectual innovation among both its uncharacteristically young professors (mostly in their thirties) and its gifted students. Berlin was built on a solid German tradition that had already extended and modernized the university ideal… Thus the hopes of all Prussia were focused on the new university at Berlin, the first to be built around the library and laboratory rather than the catechistic classroom. The university offered entering students the challenge of research rather than learning by rote, the promise of discovering new truths rather than propagating old ones. (Billington page 225)

What is most important to note for our narrative, is that prior to the Prussian innovations, education had been mostly a private matter not controlled by or even involving government. It was informally pursued through self-learning, apprenticeships, perhaps local teachers offering classes or tutors (for the wealthier) in ones youth. And if privilege and academic inclination allowed, in colleges and universities mostly run by or in the context of religious denominations.

The Prussian System Comes to America

It is interesting to note that one could argue that the U.S. today has a de facto three-tiered education system that mirrors the one the Prussians invented in the early 19th century.

* Tier one would be our elite private prep schools and elite private (and top public) universities that, though they are not completely limited to our society’s social elite, are still generally bastions of the most privileged in our country, including many of our top political leadership.

* Tier two would be the best of our public K-12 schools, located mostly in more prosperous neighborhoods, which have the resources to assist the most academically inclined of the children of the middle class to put them on the programmed path to get their degrees and then get good jobs as doctors and lawyers and other “knowledge workers”, our contemporary “apparatchiks”.

* Tier three would be the rest of our public schools, mainly in the inner cities and poor rural areas, generally under resourced and failing (by design as it is argued by some). Though there are the occasional exceptions of schools or individual students that rise above these circumstances into the second tier, which perpetuate the myth that anyone can succeed, many of our youth in these schools have the odds of success heavily stacked against them. From these ranks many of our lower-paid worker-bees come, including many of the enlisted soldiers in our volunteer army.

And further, our own modern university system was patterned after the research-oriented government supported system created by the Prussians. Here’s Gatto’s take…

The Prussian System Comes to America

It is interesting to note that one could argue that the U.S. today has a de facto three-tiered education system that mirrors the one the Prussians invented in the early 19th century.

* Tier one would be our elite private prep schools and elite private (and top public) universities that, though they are not completely limited to our society’s social elite, are still generally bastions of the most privileged in our country, including many of our top political leadership.

* Tier two would be the best of our public K-12 schools, located mostly in more prosperous neighborhoods, which have the resources to assist the most academically inclined of the children of the middle class to put them on the programmed path to get their degrees and then get good jobs as doctors and lawyers and other “knowledge workers”, our contemporary “apparatchiks”.

* Tier three would be the rest of our public schools, mainly in the inner cities and poor rural areas, generally under resourced and failing (by design as it is argued by some). Though there are the occasional exceptions of schools or individual students that rise above these circumstances into the second tier, which perpetuate the myth that anyone can succeed, many of our youth in these schools have the odds of success heavily stacked against them. From these ranks many of our lower-paid worker-bees come, including many of the enlisted soldiers in our volunteer army.

And further, our own modern university system was patterned after the research-oriented government supported system created by the Prussians. Here’s Gatto’s take…

Throughout nineteenth-century Prussia, its new form of education seemed to make that warlike nation prosper materially and militarily. While German science, philosophy, and military success seduced the world, thousands of prominent young Americans made the pilgrimage to Germany to study in its network of research universities, places where teaching and learning were always subordinate to investigations done on behalf of business and the state. Returning home with the coveted German Ph.D., those so degreed became university presidents and department heads, took over private industrial research bureaus, government offices, and the administrative professions. (Gatto page 139)

But back to our narrative…

Prussia had a great influence on the educational system in America. Here is Barzun’s take on that influence…

Prussia had a great influence on the educational system in America. Here is Barzun’s take on that influence…

The American intellectual class that did exist in the 1830s looked less and less to England and France for ideas. It was Germany that fed them… Chief among American Germanists was professor George Ticknor of Harvard. He, George Bancroft (later the first national historian), and a few others had gone to German universities and carried home the message of Herder and Goethe, Kant and Schiller in all its poetical and philosophical strength. Ticknor in turn imparted it to young Emerson and his classmates. (Barzun page 504)

One of those contemporaries of Emerson was fellow Unitarian Horace Mann, who visited Prussia in 1843 with the intent of studying their schools and bringing the best of their state-of-the-art education system back to America. I go into Mann and the context of Massachusetts in the 1830s in detail in my previous piece, “The Myth of the Common School”. He of course championed and launched the first universal compulsory state run education system in America. Again a key point here is that prior to that launch, as I mentioned before, education was mostly a local and/or personal matter, informally pursued through self-learning, apprenticeships, or teachers accepting students for classes or tutoring. For us today, five to seven generations into ubiquitous state-run K-12 public schools in every neighborhood, it is hard for us to even imagine a world where education was personal or local, rather than the business of the state. It was Mann and his like-minded comrades in the Massachusetts elite, who imagined education as a tool of an emerging republic to develop its human resources and direct that development. They saw themselves as the best and the brightest, so who better than they to say what education should be for everyone else.

In Bob Pepperman Taylor’s book Horace Mann’s Troubling Legacy, he talks about how Mann tied the fate of democracy to the fate of the common school…

In Bob Pepperman Taylor’s book Horace Mann’s Troubling Legacy, he talks about how Mann tied the fate of democracy to the fate of the common school…

Common Schools derive their value from the fact, that they are an instrument, more extensively applicable to the whole mass of the children, than any other instrument ever yet devised. They are an instrument, by which the good men in society can send redeeming influences to those children, who suffer under the calamity of vicious parentage and evil domestic associations… They are the only civil institution, capable of extending its beneficent arms to embrace and to cultivate in all parts of its nature, every child that comes into the world. Nor can it be forgotten, that there is no other instrumentality, which has done or can do so much, to inspire that universal reverence for knowledge, which incites to its acquisition. (Taylor page 34)

Though the Prussians saw their new state-run education system as a tool of their totalitarian state, Mann and other American leaders who were enamored with that system, believed a state controlled education system could be a similarly effective tool to forge a budding republic that was a melting put for a diverse population of immigrants.

Building to his discussion of the Prussian schools in the Seventh Annual Report, Mann is careful to acknowledge that regardless of the strength of their educational program, schools in Prussia were employed in the service of an authoritarian state. His claim, however, is that such schools would be all the more appropriate in a free, democratic society. He is also careful to praise our own tradition of common schools and to emphasize their egalitarian structure. “Massachusetts has the honor of establishing the first system of Free Schools in the world… Our system, too, is one and the same for both rich and poor; for, as all human beings, in regard to their natural rights, stand upon a footing of equality before God, so, in this respect, the human has been copied from the divine plan of government, by placing all citizens on the same footing of equality before the law of the land”. (Taylor page 34)

Whether authoritarian or more egalitarian, it was still a new conception of education as a function of the state, exercising top-down control of every aspect of the curriculum, pedagogy and governance of the educational process. Opponents of this radical “Prussian” approach to education called this out. Conservative Episcopalian and Massachusetts state education board member Edward Newton challenged the democratizing tendencies of Mann’s vision of the common schools…

Newton makes an additional political argument, premised on the assumption that the schools in Massachusetts were in fine shape prior to the establishment of the board and the appointment of the secretary. This being the case, the creation of the state Board of Education was a political rather than an educational decision, one designed to build and consolidate the power of the state. “We do not need this central, all-absorbing power; it is anti-republican in all its bearings, well adapted, perhaps, to Prussia, and other European despotisms, but not wanted here”. This reference to Prussia, of course, is intended to remind the reader of Mann’s praise of Prussian schools in the Seventh Annual Report released earlier in that year. (Taylor page 50)

Mann and his supporters triumphed in that dialog, and from this point forward in American history, education would be a matter controlled by the states, and increasingly in recent years by the federal government as well. As such it moved from the realm of personal development, family or community life, into the political arena of state policy and social engineering. And given the prevailing Calvinist morality in American culture, author Ron Miller in his book “What are Schools For?” says that in sharp contrast to Europe…

American politics and reform movements have traditionally defined social problems as problems of personal morality and discipline, and therefore have often failed to address the ideological or economic sources of the conflict. This moralistic approach has chronically prescribed religious authority and education rather than consider fundamental institutional change to remedy serious social problems.

American education would become the main tool to address these issues. Inspired by the Prussians who had been inspired themselves by Napoleon, that tool would be wielded by the state, and all aspects of the educational system – curriculum, pedagogy and governance – would fall under a top-down control model of state responsibility, rather than being an individual, family or local community responsibility. In a country inspired by moving away from controlling hierarchies towards a circle of equals, human development would continue to be managed in an all encompassing educational hierarchy, as it still is today.

Tags: american education system, american history, common schools, education history, Horace Mann, napoleon, public schools

No comments:

Post a Comment