“One of the misconceptions of popular history is that concern for hygiene and sanitation is a recent – and decidedly modern – phenomenon.” Simon Thurley

We don’t often think about the Tudors as being particularly hygienic people but they were actually a lot ‘cleaner’ than what we generally give them credit for. They were of course limited by the technology of the time and the challenges associated with disposing of the sewage and rubbish of a growing population but this does not mean that they did not try to keep themselves and their houses clean.

According to Alison Sim, the Tudors washed themselves a lot more often that what is generally thought. How often is not exactly known but the fact that recipes for soap and ‘hand or washing waters’ are included in household instruction manuals illustrate that there was definitely an interest in personal hygiene (Sim, Pg. 47).

Wealthy ladies used a scented toilet soap or ‘castill soap’ for their daily wash. Not all levels of society could use this type of soap, as it was imported and very expensive. The soap was made with ‘olive oil rather than the animal fat used in laundry soap’ (Sim, Pg. 47).

In Hugh Plat’s Delightes for Ladies, a 14th century household manual, he gives directions for preparing washing water suggesting the use of ‘sage, marjoram, camomile, rosemary and orange peel as possible ingredients.’ He also offers an alternative that is ‘very cheap’ once again suggesting that it was not only the wealthy Tudors that were interested in personal hygiene but people from all levels of society.

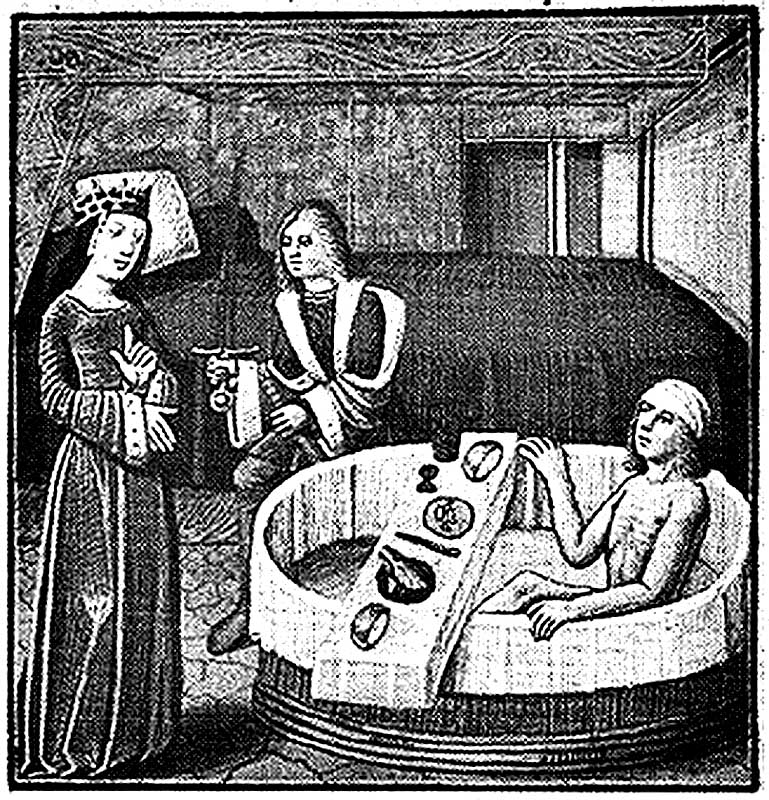

In order to have a bath most Tudors would have had to find a wooden tub, line it with sheets, collect buckets of water, heat the water by the fireplace and fill the tub. It’s probably safe to assume that this complicated process probably dissuaded people from bathing daily. There was though nothing stopping them from washing daily. The distinction being that bathing required a person to immerse themselves in a tub and washing was more like a sponge bath.

The only Tudors lucky enough to have permanent plumbing and luxurious bathrooms were royalty.

Because the water-supply determined how long the Court could stay in any one location, Henry VIII decided to overhaul the water supply systems of all of his greater houses.

Improvements made to the water supply led to improved facilities for bathing. Some of the houses Henry inherited already contained luxurious bathrooms such as Edward III’s bathroom at Westminster supplied with “2 large bronze taps for the kings bath to bring hot and cold water into the baths” (Thurley, Pg. 167).

In 1529, Henry VIII ordered a new bathroom built on the first floor of the Bayne Tower at Hampton Court. This tower was Henry VIII’s luxury suite and consisted of an office and strong-room; a bedroom, bathroom and private study and a library and jewel house (Thurley, Pg. 170).

Thurley describes the bathroom in great detail

“The Bathroom had deep window-seats with cupboards beneath and a ceiling decorated with gold battens on a white background. The baths were made by a cooper and were attached to the wall; they were supplied by two taps, one for cold water and one for hot. Directly behind the bathroom, in another small room, was a charcoal- fired stove, or boiler, fed from a cistern on the second floor which was filled by the Coombe conduit.” (Pg. 170)

Other similar bathrooms existed at the Tower of London, Windsor Castle and New Hall.

Later in Henry’s reign he started bathing in sunken baths. Thomas Platter describes Henry’s bath at Woodstock:

“We were shown King Henry VIII’s bathing-tub and bathing room, also a large square lead cistern full of water in which he bathed; the water comes from Rosamund spring, is cold in summer and warm in winter.” (Thurley, Pg. 170)

In the1540’s, Henry VIII installed a bath at Whitehall more luxurious and sophisticated than even the Hampton Court bath but we are still none the wiser as to how often Henry actually used the baths.

Thurley states that Henry, on medical advice, took ‘medicinal herbal baths’ each winter but avoided baths if the sweating sickness reared its ugly head.

A school of though existed at the time that believed that bathing was dangerous and a time that “allowed the venomous airs to enter and destroyeth the lively spirits in man and enfeebleth the body” (Thurley, Pg. 171).

Apart from bathing with scented soap, the wealthier Tudors could also afford to buy perfume. Scents were made using imported spices and so not everyone could afford such a luxury. Alison Sim believes they were used as a demonstration of one’s wealth rather than as a way of masking unpleasant odours. Sim states that if they were used to mask smells at all then it was more likely to have been the clothes rather than the people that smelt.

I imagine that wearing Tudor clothes in peak summer would have been a very sweaty affair and to try and keep the clothes smelling fresh, without the modern conveniences of deodorant, a washing machine or a dry cleaner, would have been very difficult. One way to try and remain fresh would have involved changing your undergarments as often as possible.

Whether you were wealthy or not you wore a linen undergarment called a smock or shirt (Sim, Pg. 52). The Tudors took great care in ensuring their linen was clean as it was a sign of one’s respectability. In Richard Jones’ book, Heptameron of Civil Discourses, a book about how to have a happy marriage, he says that a woman who does not wear clean linen ‘shal neither be prazed of strangers, or delight her husband’ (Sim, Pg. 52). Most would try and change their linen daily and the wealthier would have changed their linen several times per day.

In the next part of our Tudor hygiene article we will look at how the Tudors brushed their teeth, the clothes washing practices of the day and how general household cleaning was done.

References

Sim, A. The Tudor Housewife, 2010.

Thurley, S. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: Architecture and Court Life, 1993.

No comments:

Post a Comment