The Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (1803) [1] was a land deal between the United States and France, in which the U.S. acquired approximately 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million dollars.

"This little event, of France's possessing herself of Louisiana, is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both sides of the Atlantic and involve in it's effects their highest destinies."[2]

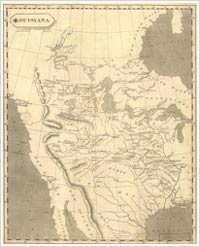

1805 Map of Louisiana by Samuel Lewis; courtesy the Library of Congress

1805 Map of Louisiana by Samuel Lewis; courtesy the Library of Congress

President Thomas Jefferson wrote this prediction in an April 1802 letter to Pierre Samuel du Pont amid reports that Spain would retrocede to France the vast territory of Louisiana. As the United States had expanded westward, navigation of the Mississippi River and access to the port of New Orleans had become critical to American commerce, so this transfer of authority was cause for concern. Within a week of his letter to du Pont, Jefferson wrote U.S. Minister to France Robert Livingston: "Every eye in the U.S. is now fixed on this affair of Louisiana. Perhaps nothing since the revolutionary war has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation." [3]

BACKGROUND

The presence of Spain was not so provocative. A conflict over navigation of the Mississippi had been resolved in 1795 with a treaty in which Spain recognized the United States' right to use the river and to deposit goods in New Orleans for transfer to oceangoing vessels. In his letter to Livingston, Jefferson wrote, "Spain might have retained [New Orleans] quietly for years. Her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce her to increase our facilities there, so that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us."[4] He went on to speculate that "it would not perhaps be very long before some circumstance might arise which might make the cession of it to us the price of something of more worth to her."[5]

Napoleon Bonaparte; courtesy the Library of Congress

Napoleon Bonaparte; courtesy the Library of Congress

Jefferson's vision of obtaining territory from Spain was altered by the prospect of having the much more powerful France of Napoleon Bonaparte as a next-door neighbor.

France had surrendered its North American possessions at the end of the French and Indian War. New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi were transferred to Spain in 1762, and French territories east of the Mississippi, including Canada, were ceded to Britain the next year. But Napoleon, who took power in 1799, aimed to restore France's presence on the continent.

The Louisiana situation reached a crisis point in October 1802 when Spain's King Charles IV signed a decree transferring the territory to France and the Spanish agent in New Orleans, acting on orders from the Spanish court, revoked Americans' access to the port's warehouses. These moves prompted outrage in the United States.

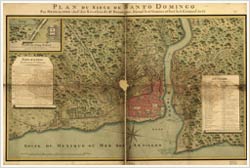

1815 Plan of New Orleans by I. Tanesse; courtesy the Library of Congress

1815 Plan of New Orleans by I. Tanesse; courtesy the Library of Congress

While Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison worked to resolve the issue through diplomatic channels, some factions in the West and the opposition Federalist Party called for war and advocated secession by the western territories in order to seize control of the lower Mississippi and New Orleans.

NEGOTIATIONS

Aware of the need for action more visible than diplomatic maneuvering and concerned with the threat of disunion, Jefferson in January 1803 recommended that James Monroe join Livingston in Paris as minister extraordinary. (Later that same month, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition that would cross the Louisiana territory, regardless of who controlled it, and proceed on to the Pacific. This would become the Lewis and Clark Expedition.) Monroe was a close personal friend and political ally of Jefferson's, but he also owned land in Kentucky and had spoken openly for the rights of the western territories.

Jefferson urged Monroe to accept the posting, saying he possessed "the unlimited confidence of the administration and of the western people."[6] Jefferson added: "All eyes, all hopes, are now fixed on you, for on the event of this mission depends the future destinies of this republic."[7]

Shortly thereafter, Jefferson wrote to Kentucky's governor, James Garrard, to inform him of Monroe's appointment and to assure him that Monroe was empowered to enter into "arrangements that may effectually secure our rights & interest in the Mississippi, and in the country eastward of that."[8]

As Jefferson noted in that letter, Monroe's charge was to obtain land east of the Mississippi. Monroe's instructions, drawn up by Madison and approved by Jefferson, allocated up to $10 million for the purchase of New Orleans and all or part of the Floridas. If this bid failed, Monroe was instructed to try to purchase just New Orleans, or, at the very least, secure U.S. access to the Mississippi and the port.

But when Monroe reached Paris on April 12, 1803, he learned from Livingston that a very different offer was on the table.

Napoleon's plans to re-establish France in the New World were unraveling. The French army sent to suppress a rebellion by slaves and free blacks in the sugar-rich colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) had been decimated by yellow fever, and a new war with Britain seemed inevitable. France's minister of finance, Francois de Barbé-Marbois, who had always doubted Louisiana's worth, counseled Napoleon that Louisiana would be less valuable without Saint Domingue and, in the event of war, the territory would likely be taken by the British from Canada. France could not afford to send forces to occupy the entire Mississippi Valley, so why not abandon the idea of empire in America and sell the territory to the United States?

Napoleon's plans to re-establish France in the New World were unraveling. The French army sent to suppress a rebellion by slaves and free blacks in the sugar-rich colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) had been decimated by yellow fever, and a new war with Britain seemed inevitable. France's minister of finance, Francois de Barbé-Marbois, who had always doubted Louisiana's worth, counseled Napoleon that Louisiana would be less valuable without Saint Domingue and, in the event of war, the territory would likely be taken by the British from Canada. France could not afford to send forces to occupy the entire Mississippi Valley, so why not abandon the idea of empire in America and sell the territory to the United States?

Napoleon agreed. On April 11, Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand told Livingston that France was willing to sell all of Louisiana. Livingston informed Monroe upon his arrival the next day.

Seizing on what Jefferson later called "a fugitive occurrence," Monroeand Livingston immediately entered into negotiations and on April 30 reached an agreement that exceeded their authority - the purchase of the Louisiana territory, including New Orleans, for $15 million. The acquisition of approximately 827,000 square miles would double the size of the United States.

Though rumors of the purchase preceded notification from Monroe and Livingston, their message reached Washington in time for an official announcement on July 4, 1803.

The purchase treaty had to be ratified by the end of October, which gave Jefferson and his Cabinet time to deliberate the issues of boundaries and constitutionality. Exact boundaries would have to be negotiated with Spain and England and so would not be set for several years, and Jefferson's Cabinet members argued that the constitutional amendment he proposed was not necessary. As time for ratification of the purchase treaty grew short, Jefferson accepted his Cabinet's counsel and rationalized: "It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; and saying to him when of age, I did this for your good."[9] .

The purchase treaty had to be ratified by the end of October, which gave Jefferson and his Cabinet time to deliberate the issues of boundaries and constitutionality. Exact boundaries would have to be negotiated with Spain and England and so would not be set for several years, and Jefferson's Cabinet members argued that the constitutional amendment he proposed was not necessary. As time for ratification of the purchase treaty grew short, Jefferson accepted his Cabinet's counsel and rationalized: "It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; and saying to him when of age, I did this for your good."[9] .

The Senate ratified the treaty on October 20th by a vote of 24 to 7. Spain, upset by the sale but without the military power to block it, formally returned Louisiana to France on November 30th. France officially transferred the territory to the Americans on December 20th, and the United States took formal possession on December 30th.

Jefferson's prediction of a "tornado" that would burst upon the countries on both sides of the Atlantic had been averted, but his belief that the affair of Louisiana would impact upon "their highest destinies" proved prophetic indeed.

TIMELINE OF THE LOUISIANA TERRITORY[10]

1682 René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, claims for France all territory drained by Mississippi River from Canada to Gulf of Mexico and names it Louisiana.

1718 New Orleans is founded.

1762 France cedes New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi to Spain.

1763 France cedes territories east of the Mississippi and north of New Orleans to Britain.

1783 Treaty of Paris gives newly independent United States free access to the Mississippi.

1784 Spain closes lower Mississippi and New Orleans to foreigners.

1789 French Revolution begins.

1790 Slaves revolt on Caribbean island of Saint Domingue, France's richest colony.

1795 Spain reopens the Mississippi and New Orleans to Americans.

1799 Napoleon Bonaparte seizes power in France.

1800 Spain secretly agrees to return Louisiana to France in exchange for Eturia, a small kingdom in [[Italy]].

1801 President Jefferson names Robert Livingston minister to France.

1802 Spain cedes Louisiana to France. New Orleans is closed to American shipping. French army sent to re-establish control in Saint Domingue is decimated.

Events of 1803

January Jefferson sends James Monroe to join Livingston in France.

February Napoleon decides against sending more troops to Saint Domingue and instead orders forces to sail to New Orleans.

March Napoleon cancels military expedition to Louisiana.

April 11 Foreign Minister Talleyrand tells Livingston that France is willing to sell all of Louisiana.

April 12 Monroe arrives in Paris and joins Livingston in negotiations with Finance Minister Barbé-Marbois.

April 30 Monroe, Livingston, and Barbé-Marbois agree on terms of sale: $15 million for approximately. 827,000 square miles of territory.

May 18 Britain declares war on France.

July 4 Purchase is officially announced in United States. October 20U.S. Senate ratifies purchase treaty.

November 30 Spain formally transfers Louisiana to France.

December 20 France formally transfers Louisiana to United States.

December 30 United States takes formal possession of Louisiana.

Footnotes

1. The following material is based on Gaye Wilson, "Jefferson's Big Deal: The Louisiana Purchase", Monticello Newsletter, 14 (Spring 2003).

2. Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert E. Bergh, eds. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903-04), 10:318.

4. Ibid, 10:312.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid, 10:344.

7. Ibid.

8. Paul Leicester Ford, ed. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892-99), 8:203.

10. This section is based on Gaye Wilson, "Timeline Louisiana Territory", Monticello Newsletter, 14 (Spring 2003).

FURTHER SOURCES

- Bond, Bradley G., ed. French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005

- Cunningham, Cunningham, Noble, Jr. Jefferson and Monroe: Constant Friendship and Respect. Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2003.

Available for purchase at Museum Shop - Fleming, Thomas. The Louisiana Purchase. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Lewis, James E, Jr. Louisiana Purchase: A Noble Bargian. Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2003. Available for purchase at Museum Shop

- Rodriquez, Junius P, ed. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2002.

- Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Timeline of Louisiana Purchase.

- Find additional sources in the Thomas Jefferson Portal.

No comments:

Post a Comment