http://www.crystalinks.com/henge.html

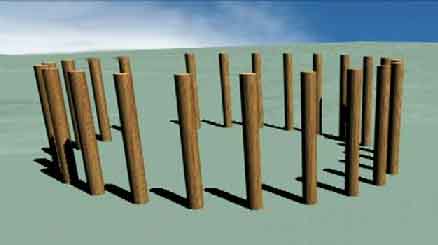

A henge is a roughly circular or oval-shaped flat area over 20m in diameter which is enclosed and delimited by a boundary earthwork that usually comprises a ditch with an external bank. Access to the interior is obtained by way of one, two, or four entrances through the earthwork. Internal components may include portal settings, timber circles, post rings, stone circles, four-stone settings, monoliths, standing posts, pits, coves, post alignments, stone alignments, burials, central mounds, and stakeholes.

Given the defensive impracticalities of an enclosure with an external bank and internal ditch (rather than vice versa), henges are considered to have served a ritual purpose, perhaps built with intention of shielding what went on inside the enclosure from the outside world.

British enthusiasts, such as the editors of the Penguin Dictionary of Archaeology, claim that henges are unique to the British Isles and that similar, much earlier, circles on the Continent, such as Goseck circle are not proper "henges".

Another such enthusiast is Julian Cope whose book, The Megalithic European, proposes that the henge was a regional development from the Europe-wide causewayed enclosure, appearing following a cultural upheaval in around 3000 BC which inspired the peoples of Neolithic Europe to develop more independently.

He mentions the 'rondel enclosures' of Bavaria's Isar Valley which according to investigations by the German archaeologist RA Maier "drew comparisons with the henge monuments and causewayed enclosures of the British Isles". Although still with a multiply-causewayed ditch and entrances at cardinal points, the roundels are described by John Hodgson as not being positioned with defensive aims in mind and the largest, at Kothingeichendorf, appeared to be "midway between a henge and a causewayed enclosure".

Alasdair Whittle also views the development of the henge as a regional variation within a European tradition that included a variety of ditched enclosures. He notes that henges and the grooved ware pottery often found at them are two examples of the British Neolithic not found on the Continent.

Caroline Malone also states that henges did not occur in the rest of Western Europe but developed from a broader tradition of enclosure to become a phenomenon of the British Isles, a native tradition with sophisticated architecture and calendrical functions.

Efforts to provide a direct lineage for the henge from earlier enclosures have not been entirely conclusive; their chronological overlap with older structures making it difficult to see them as a coherent tradition. They seem to take the concept of creating a space separate from the outside world one step further than the causewayed enclosure and firmly focus attention on an internal point.

In some cases, the construction of the bank and ditch was a stage that followed other activity on the site. Balfarg, North Mains and Cairnpapple earlier cremations and deliberate smashing of pottery predate the enclosure.

Henges are concentrated in southern England although they are also found all over the British Isles and Orkney is sometimes suggested as the original provenance of the monument type. Unlike earlier enclosure monuments they were not built on hilltops but on low-lying ground often close to watercourses and good agricultural land.

Henges often contain evidence of a variety of internal features including timber or stone circles, pits or burials. They should not be confused with the stone circles which are sometimes present within them. Similarly shaped, but larger enclosures are known as Henge enclosures whilst smaller ones with other types of enclosing features are known as Hengiform monuments.

The word henge is a backformation from Stonehenge, the famous monument in Wiltshire. Stonehenge is not a true henge at all as its ditch runs outside its bank, although there is a small extant external bank as well. This is a modern distinction however, we do not know if ditch placement would have been a significant feature or not to the people who built the monuments. The term to was first coined in 1932 by Thomas Kendrick who later became the Keeper of British Antiquities at the British Museum.

Some of the finest and best-known henges include:

- Avebury, about 20 miles N. of Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain;

- Durrington Walls near Woodhenge also on Salisbury Plain;

- Maumbury Rings in Dorset (later reused as a Roman amphitheatre and then a Civil War fort).

- Mayborough in Cumbria

- The Ring O'Bookan in Orkney;

- Thornborough Henge complex in Yorkshire;

- Woodhenge Wiltshire

- The Great Circle at Stanton Drew in Wiltshire where crop circles are often found

At King Arthur's Round Table, Cumbria, a cremation trench lay within the monument, while at Woodhenge a central burial of a child was interpreted by its excavators as a dedicatory offering. Phosphate surveys at Maxey henge suggested that burials may also have been present within this monument.

Stone circles are also found within a few henges, with at least six cases identified in England.

- A stone circle is a circular space, delimited by purposely erected stones and often containing burials. They should not be confused with henges or isolated monoliths, although all these features are often encountered together. Nor should they be confused with earlier rings, such as the Goseck circle in Saxony-Anhalt, that may have served similar religious/calendrical/astronomical purposes, though at a much earlier epoch.

Archaeological evidence, coupled with information from astronomers, geologists and mathematicians, implies that the purpose of stone circles was connected with prehistoric peoples' beliefs and that their construction can shed light on ancient engineering, social organisation, religion and, for want of a better word, science. Their precise function however will probably always remain open to debate.

Prehistoric stone circles are found as megalithic monuments in the British Isles, with two confirmed examples in Brittany on the island of Er Lannic and two more suggested at Carnac. The Petit Saint Bernard circle lies further afield, in the French Alps. A unique form of circle, the recumbent stone circle is to be found in North East Scotland, where the largest stone is on its side.

In Scandinavia, there was a tradition of making stone circles during the Iron Age and especially in Gotaland. The appearance of these circles in northern Poland is considered to be a characteristic of the migrating Goths (see Stone Circle (Iron Age) and Wielbark Culture).

They are also known in the Basque country, where the villagers attribute their construction to jentils and mairus, giants of the pre-Christian era.There was a separate period of stone circle building from the eighth to the twelfth century in West Africa. The best known are the Senegambian stone circles, built as funerary monuments, with more than a thousand known. Other stone circles can be found on the Adrar Plateau in Mauritania.

Stone circle construction has become popular since the 1970s, built either for purely monumental purposes or to serve a particular mystical purpose. The new stone circles typically lack henges or other auxiliary features and are not on a particular alignment. Notable examples include the Swan Circle at the Glastonbury Festival, while Stonehenge at Maryhill (ultimately built of concrete rather than stone) is an early example, being completed in 1918.

The French archaeologist Jean-Pierre Mohan in his book Le Monde des Megalithes described the unusual concentration of stone circles in the British Isles as follows:British Isles megalithism is outstanding in the abundance of standing stones, and the variety of circular architectural complexes of which they formed a part...strikingly original, they have no equivalent elsewhere in Europe - strongly supporting the argument that the builders were independent.

Often oriented on sight lines for the rising or setting sun or moon at certain times of the year, it seems likely that for their builders, fertility and the cycle of life were very important concepts. The crudeness of the stones means that they could not have been used as advanced astronomical calculators however, and their positioning is more symbolic than functional.

The earliest circles were erected around five thousand years ago during the Neolithic period and may have evolved from earlier burial mounds which often covered timber or stone mortuary houses.

During the Middle Neolithic (c. 3700-2500 BC) stone circles began to appear in coastal and lowland areas towards the north of the British Isles. The Langdale axe industry in the Lake District appears to have been an important early centre for circle building, perhaps because of its economic power. Many had closely set stones, perhaps similar to the earth banks of henges, others were made from unfounded boulders rather than standing stones.

By the later Neolithic, stone circle construction had attained a greater precision and popularity. Rather than being limited to coastal areas, they began to move inland and their builders grew more ambitious, producing examples of up to 400 m diameter in the case of the Outer Circle at Avebury. Most circles however measured around 25 m in diameter however. Designs became more complex with double and triple ring designs appearing along with significant regional variation. These monuments are often classed separately as concentric stone circles.

The final phase of stone circle construction took place in the early to middle Bronze Age (c.2200-1500 BC) and saw the construction of numerous small circles which, it has been suggested, were built by individual family groups rather than the large numbers that monuments like Avebury would have required.

Many fine examples are to be found within Dartmoor National Park, Devon - the site of 18 recorded stone circles (and 75 stone rows) dating mainly from the late Neolithic to mid-Bronze Age. Grey Wethers, a double circle on an isolated plateau, is among the most significant sites.

By 1500 BC stone circle construction had all but ceased. It is thought that changing weather patterns led people away from upland areas and that new religious thinking led to different ways of marking life and death. Stone circles have often been associated with the druids, but they were abandoned long before druidism came to Britain, and there is no evidence that they were ever used by the druids.

The alignment of henges is a contentious issue. Popular belief is that their entrances point towards certain heavenly bodies. In fact, henge orientation is highly variable and may have been more determined by local topology rather than any desire for symbolic orientation. A slight tendency for Class I henges having an entrance set in the north or north-east quarter has been identified following statistical analysis while Class II henges generally have their axes aligned approximately south east to north west or north east to south west.

It has been suggested that the stone and timber structures sometimes built inside henges were used as solar declinometers, used to measure the position of the rising or setting sun. These structures by no means appear in all henges and often considerably post-date the henges themselves. They therefore are not necessarily connected with the henge's original function. It has been conjectured that they could have been used to synchronize a calendar to the solar cycle for purposes of planting crops or timing religious rituals.

Some henges have poles, stones or entrances that would indicate the position of the rising or setting sun during the equinoxes and solstices whilst others appear to frame certain constellations. Additionally, many are placed so that nearby hills either mark or do not interfere with such observations.

Finally, some henges appear to be placed at particular latitudes. For example, a number are placed at a latitude of 55 degrees north, where the same two markers can indicate the rising and setting sun for both the spring and autumn equinoxes. Henges are present from the extreme north to the extreme south of Britain however and so their latitude could not have been of great importance.

Formalization is commonly attributed to henges; indications of the builders' concerns in controlling the arrival at, entrance to and movement within the enclosures. This was achieved through placing flanking stones or avenues at entrances of some henges or by dividing up the internal space using timber circles. While some were the first monuments to be built in their areas, others were added to already important landscapes, especially the larger examples.

The concentric nature of many of the internal features, such as the five rings of postholes at Balfarg or the six at Woodhenge, may in fact represent a finer distinction than the inside-out differences suggested by henge earthworks The ordering of space and suggestion of circular movement suggested by the sometimes densely-packed internal features indicates a sophisticated degree of spatial understanding.

Carhenge is either a modern parody or artistic tribute to the famous Stonehenge structure.

Henges Wikipedia

Henges Google Videos

Henges Google VideosIn the News ...

Archaeologists unearth Neolithic henge at Stonehenge BBC - July 22, 2010

Archaeologists unearth Neolithic henge at Stonehenge BBC - July 22, 2010

Archaeologists have discovered a second henge at Stonehenge, described as the most exciting find there in 50 years.

Wooden "Stonehenge" Emerges From Prehistoric Ohio National Geographic - July 21, 2010

It appears to be a 2,000-year-old ceremonial site.

It appears to be a 2,000-year-old ceremonial site.English archaeologists find new prehistoric site PhysOrg - October 3, 2009

- Archaeologists have discovered a smaller prehistoric site near Britain's famous circle of standing stones at Stonehenge. Researchers have dubbed the site "Bluehenge," after the color of the 27 Welsh stones that were laid to make up a path. The stones have disappeared but the path of holes remains. The site is about a mile (2 kilometers) away from Stonehenge, which is believed to have been built around 2500 B.C. Bluehenge, about 80 miles (130 kilometers) southwest of London, is thought to date back to the same period, but the exact circumstances of Bluehenge's construction aren't clear.

No comments:

Post a Comment