http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/theme/guinevere

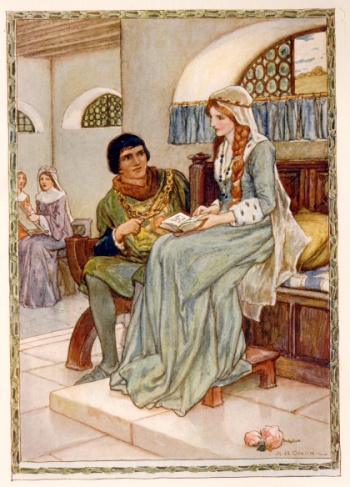

Sir Launcelot and the Queen Talked Sadly Together

by: Arthur Dixon (Artist)from: King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (Facing p. 126) - 1921

CharactersName Variants: Guenevere, Ginevra, Gwenhwyfar, Gaynor, Guanhumara, Guennivar, Ganore, Guenever, Waynor

Guinevere is said to be the daughter of Leodegrance of Cameliard in late medieval romance. In many sources, she marries Arthur and then has a love affair with Lancelot which causes the downfall of Camelot.

The Welsh Triads speak of "Arthur's Three Great Queens," all named Gwenhwyfar (Triad 56) and name Gwenhwyfar as "more faithless" than the three faithless wives of the Island of Britain (Triad 80). One of the earliest Arthurian stories is about the abduction of Guinevere by Meleagant (or Melyagaunce or Melwas). The story is told in The Life of St. Gildas (c. 1130) by Caradoc of Llancarfan and in the Welsh "Dialogue of Melwas and Gwenhwyfar." It is the subject of the earliest known Arthurian sculpture on the archivolt of the Porta della Pescheria on the Modena Cathedral. The story of the abduction is the central action in Chrétien de Troyes' Lancelot and appears in Malory.

Geoffrey of Monmouth introduces the notion of Guinevere’s infidelity (with Modred) while Arthur is fighting on the continent. In the twelfth-century Rise of Gawain, Arthur’s wife is called Gwendoloena and is said to have been initiated into sorcery and to be able to divine the future.

In Chrétien’s Lancelot, Guinevere becomes Lancelot’s lover after he rescues her from Meleagant. She is a demanding courtly lover; for example, she refuses to see Lancelot after he has suffered greatly in saving her because he hesitated two steps before leaping into a cart on his quest to rescue her, thus suggesting that his love was not absolute. But she loves deeply and contemplates suicide when she hears rumors of Lancelot’s death.

Although generally in the romance tradition, Guinevere is portrayed as Lancelot’s lover, that is not the case in Ulrich von Zatzikhoven’s Lanzelet. Ginover, who fails the chastity test of the mantle, she is said to have erred only in thought. The nature of those thoughts is not revealed, but she and Arthur have a son and seem to be happily married. And she is an intimate friend of Lanzelet’s beloved Yblis. Lanzelet does champion Ginover, but when she is abducted by Valerin, Arthur leads the expedition to rescue her and Lanzelet plays only a minor role.

In the Vulgate Cycle, the first meeting between Guinevere and Lancelot is arranged by Galehaut, and Guinevere subsequently arranges for Galehaut and the Lady of Malehaut to become lovers. She is later accused of not being the true Guinevere by the illegitimate daughter of her father Leodagan and the wife of his seneschal. When Arthur falls in love with the False Guinevere and accepts her as his queen, Guinevere is protected by Lancelot and Galehaut until the truth is revealed. Lancelot assists Guinevere again by rescuing her when she is abducted by Meleagant. In the Mort Artu, after Guinevere is found to be Lancelot’s lover and condemned to be burned to death, Lancelot rescues her again and takes her to Joyous Guard, but the Pope demands that Arthur be reconciled with her. When Arthur leaves for France to attack Lancelot, Mordred tries to claim the throne and to marry Guinevere. She flees to the Tower of London and then, when Arthur returns, to a convent, where she dies.

Malory’s Guinevere is jealous and demanding but also a true lover. Her jealousy and anger drive Lancelot mad and lead her to say she wishes he were dead. Nevertheless, she remains true to him. She is accused several times of crimes—infidelity and the murder of Mador’s relative—and must be saved by Lancelot, as she is once again when their love is discovered and she is sentenced to be burned at the stake. When Mordred rebels against Arthur and attempts to marry her, she flees first to the Tower of London and then to the nunnery at Amesbury, where she becomes abbess. Lancelot visits her there after the death of Arthur, but she asks him to leave and never to return and refuses even to give him a final kiss. She dies a holy death, of which Lancelot learns in a vision that instructs him to have her buried next to Arthur.

While Malory is understanding of the true love of Guinevere, Tennyson makes her an example of an unfaithful wife. His Guinevere believes that "He is all fault who hath no fault at all" and wants her lover to "have a touch of earth." Arthur, before whom she grovels with guilt when he visits her in the nunnery, says that she has "spoilt the purpose of my life." Nevertheless, Tennyson does bring Guinevere and other female characters to the fore, as does one of his contemporaries, William Morris. In his poem "The Defence of Guenevere," Morris is the first to give the Queen her own voice, thus beginning a tradition that is continued in Sara Teasdale's poem "Guenevere," Dorothy Parker's "Guinevere at Her Fireside," and Wendy Mnookin's collection Guenever Speaks, as well as in many contemporary novels told from Guinevere's point of view, such as Parke Godwin's Beloved Exile and Persia Wooley's Guinevere trilogy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahern, Stephen. “Listening to Guinevere: Female Agency and the Politics of Chivalry in Tennyson’s Idylls.” Studies in Philology 101.1 (2004): 88-112.

Archibald, Elizabeth. "Malory's Lancelot and Guenevere." In A Companion to Arthurian Literature. Ed. Helen Fulton. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Pp. 312-25.

Cross, Tom Peete and William Albert Nitze. Lancelot and Guenevere: A Study on the Origins of Courtly Love. 1930; rpt. New York: Phaeton Press, 1970.

Fulton, Helen. “A Woman’s Place: Guinevere in the Welsh and French Romances.”Quondam et Futurus: A Journal of Arthurian Interpretations 3.2 (1993): 1-25.

Gordon-Wise, Barbara Ann. The Reclamation of a Queen: Guinevere in Modern Fantasy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991.

Hoberg, Tom. “In Her Own Right: The Guinevere of Parke Godwin. In Popular Arthurian Traditions. Ed. Sally K. Slocum. Bowling Green, OK: Popular Press, 1992. Pp. 68-79.

Hodges, Kenneth. “Guenevere’s Politics in Malory’s Morte Darthur. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 104.1 (2005): 54-79.

Korrel, Peter. An Arthurian Triangle: A Study of the Origin, Development and Characterization of Arthur, Guinevere and Modred. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1984.

Lancelot and Guinevere: A Casebook. Ed. Lori J. Wlaters. New York: Garland, 1996.

Noble, James. “Guinevere, the Superwoman of Contemporary Arthurian Fiction.”Florilegium 23.2 (2006): 197-210.

Ranum, Ingrid. “Tennyson’s False Women: Vivien, Guinevere, and the Challenge to Victorian Domestic Ideology.” Victorian Newsletter 117 (201): 39-56.

Samples, Susann. "Guinevere: A Re-Appraisal." Arthurian Interpretations 3.2 (1989): 106-18.

Sasso, Eleonora. “Tennyson, Morris and the Guinevere Complex.” Tennyson Research Bulletin 9:3 (2009): 271-27.

Shichtman, Martin B. “Elaine and Guinevere: Gender and Historical Consciousness in the Middle Ages.” In New Images of Medieval Women: Essays towards a Cultural Anthropology. Ed. Edelgard E. DuBruck. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1989. Pp. 255-71.

Skinner, Veronica L. “Guinevere’s Role in the Arthurian Poetry of Charles Williams. Mythlore 4.3 (1977): 9-11.

Archibald, Elizabeth. "Malory's Lancelot and Guenevere." In A Companion to Arthurian Literature. Ed. Helen Fulton. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Pp. 312-25.

Cross, Tom Peete and William Albert Nitze. Lancelot and Guenevere: A Study on the Origins of Courtly Love. 1930; rpt. New York: Phaeton Press, 1970.

Fulton, Helen. “A Woman’s Place: Guinevere in the Welsh and French Romances.”Quondam et Futurus: A Journal of Arthurian Interpretations 3.2 (1993): 1-25.

Gordon-Wise, Barbara Ann. The Reclamation of a Queen: Guinevere in Modern Fantasy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991.

Hoberg, Tom. “In Her Own Right: The Guinevere of Parke Godwin. In Popular Arthurian Traditions. Ed. Sally K. Slocum. Bowling Green, OK: Popular Press, 1992. Pp. 68-79.

Hodges, Kenneth. “Guenevere’s Politics in Malory’s Morte Darthur. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 104.1 (2005): 54-79.

Korrel, Peter. An Arthurian Triangle: A Study of the Origin, Development and Characterization of Arthur, Guinevere and Modred. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1984.

Lancelot and Guinevere: A Casebook. Ed. Lori J. Wlaters. New York: Garland, 1996.

Noble, James. “Guinevere, the Superwoman of Contemporary Arthurian Fiction.”Florilegium 23.2 (2006): 197-210.

Ranum, Ingrid. “Tennyson’s False Women: Vivien, Guinevere, and the Challenge to Victorian Domestic Ideology.” Victorian Newsletter 117 (201): 39-56.

Samples, Susann. "Guinevere: A Re-Appraisal." Arthurian Interpretations 3.2 (1989): 106-18.

Sasso, Eleonora. “Tennyson, Morris and the Guinevere Complex.” Tennyson Research Bulletin 9:3 (2009): 271-27.

Shichtman, Martin B. “Elaine and Guinevere: Gender and Historical Consciousness in the Middle Ages.” In New Images of Medieval Women: Essays towards a Cultural Anthropology. Ed. Edelgard E. DuBruck. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1989. Pp. 255-71.

Skinner, Veronica L. “Guinevere’s Role in the Arthurian Poetry of Charles Williams. Mythlore 4.3 (1977): 9-11.

No comments:

Post a Comment