Lady Margaret Beaufort at Prayer from the National Portrait Gallery (Image in the public domain)

Lady Margaret Beaufort was the matriarch of the Tudor dynasty of Kings in England. Her life was greatly influenced by the turning of the Wheel of Fortune. That she managed to survive the vagaries of the War of Roses in England is something at which to be marveled. We have the memories of her confessor, John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester and Margaret gave him permission to share these memories after her death. Fisher saw the emotional Margaret but most people saw the steely, self-controlled Margaret of politics. She had great presence and a forceful personality. She was skilled and effective and could be ruthless.

Margaret was born on May 31, 1443 at Bletso in Bedfordshire. She was the daughter of John, Earl of Somerset. Somerset was a grandson of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster who was the third surviving son of King Edward III and Gaunt’s mistress and later wife, Katherine Swynford. The children of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford were legitimized after their marriage but they were unable to inherit the throne of England. Margaret’s mother was Margaret Beauchamp, the daughter and heiress of Sir John Beauchamp of the gentry. Margaret Beauchamp had been previously married to Sir Oliver St. John by whom she had seven children.

As an aristocrat, John Beaufort was to be the longest held English prisoner in France of the Hundred Years’ War. When King Henry VI finally arranged his release, he was bitter and financially strapped. The King gave him lands and offices and the title of Duke of Somerset and sent him back to France to fight and make as much money as possible. But Somerset caused trouble in France and the King was furious. When Somerset returned to England, the King refused to meet with him and he faced charges of treason. It is believed he committed suicide just a few days short of Margaret’s first birthday. Upon his death Margaret became one of the greatest heiresses in England.

King Henry granted Margaret’s wardship to one of his favorite councilors, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. There is little on record of Margaret’s upbringing but she remained in her mother’s custody and she appears to have been affectionate with her mother and her St. John half-siblings. She also received a decent education.

The Earl of Suffolk arranged a marriage between his eight year old son John de la Pole and Margaret when she was six years old. There may have been a marriage ceremony but Margaret was returned to her mother and the marriage was never consummated. When Suffolk was disgraced in April of 1450, the marriage between Margaret and John de la Pole was voided. Margaret never referred to John de la Pole as her first husband.

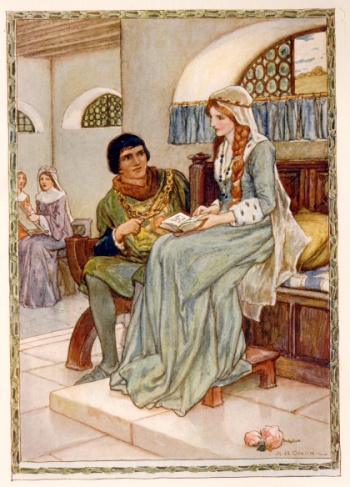

In 1453, King Henry VI granted the wardship of Margaret to his half-brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor. Presumably, King Henry intended Margaret to marry one of the Tudors and he may have considered Margaret to be a prospective heir to the throne as a surviving member of the House of Lancaster. In 1455, Margaret was married to the elder of the two brothers, twenty-two year old Edmund, 1st Earl of Richmond.

Edmund was sent to Wales by the King and took Margaret with him. Although Margaret was of a legal age to be married, she was petite and still very much a child. Edmund, in an effort to have an heir and gain the rights to Margaret’s fortune, consummated the marriage. She became pregnant in the early part of 1456. Unfortunately in August of 1456, Edmund was captured by an ally of the Duke of York. Edmund was imprisoned and later released but died of plague in early November at Carmarthen Castle. Margaret was pregnant, only thirteen and a widow. She put herself under the protection of her brother-in-law Jasper in Pembroke Castle and her son Henry Tudor was born there on January 28, 1457.

Pembroke Castles, Wales where Margaret’s son was born (Image in the public domain)

The birth of Henry had been very hard on Margaret but both mother and child survived. Margaret may have suffered permanent physical damage in the childbirth as there is no record she ever had another pregnancy or child. She spent about a year at Pembroke with her son to whom she became very devoted. She then sought, with the help of her brother-in-law, a new marriage alliance before the King forced another husband on her. An agreement was made between Margaret and the Duke of Buckingham’s second son, Henry Stafford in April of 1457 and the marriage was celebrated in January of 1458. This appears to have been a happy marriage. Margaret’s son Henry remained in the custody of his uncle Jasper in Pembroke and Margaret and her husband visited him there regularly.

In 1461, after Edward IV became King, Henry Tudor’s wardship was sold to Lord Herbert for £1000. Lord Herbert and his wife Anne Devereux supervised his upbringing in a kind and considerate way. Margaret made arrangements allowing for visits with her son and she sent regular messengers to the Herbert’s inquiring for news.

In 1466, King Edward granted the manor at Woking to Margaret and her husband. Margaret was proficient in running her household and estates and enjoyed dressing in rich clothes. In 1468, the Stafford’s entertained King Edward at Woking. In October 1470, Henry joined his mother in a visit to King Henry VI who had just been returned to the throne. Henry then returned to Pembroke. Not long after this visit, Edward IV returned with an army to reclaim the throne.

On April 18, 1471, Edward defeated the Lancastrian forces under the Earl of Warwick at the Battle of Barnet. Margaret’s husband Henry was severely wounded in the battle and returned home. After the defeat of King Henry VI’s wife Margaret of Anjou at the Battle of Tewkesbury, and the death of her son Edward of Lancaster, King Henry VI was murdered in the Tower of London. This left Margaret Beaufort and her son Henry with the best claim to be the heirs of the House of Lancaster. Jasper and Henry Tudor tried to flee to France but were blown off course and landed in Brittany. Margaret’s husband Henry Stafford died, mostly likely from his battle wounds on October 4, 1471.

Margaret’s political situation was perilous and she immediately sought a new protector. In June of 1472, Margaret married Thomas, Lord Stanley. Stanley was a major landowner in England and he managed to never lead his troops into battle for either the House of Lancaster or York. This marriage was most likely a business arrangement with Margaret getting protection for her land holdings and her wealth and Stanley getting the prestige of her name and her wealth.

Stanley was in King Edward’s circle and Margaret did attend court. Her marriage to Stanley was probably agreeable in the beginning. Margaret began working to get her son returned to favor in England. Jasper and Henry had gone to the court of Francis II, Duke of Brittany where they were treated with courtesy but essentially prisoners. Margaret didn’t see her son between 1471 and 1485 but she was in constant contact with him.

In 1476, Margaret was in sufficient favor with the Yorkist court of King Edward that she attended Queen Elizabeth Woodville during the reburial ceremony of Edward’s father the Duke of York. During the christening of Edward’s youngest child Bridget in 1482, Margaret was given the honor of holding the infant. Margaret eventually persuaded Edward to allow her son to return to England. In June of 1482, there was a draft pardon drawn up and discussion of Henry marrying Edward’s eldest daughter Elizabeth of York. But before all these arrangements could be finalized, King Edward died on April 9, 1483, leaving his twelve year old son Edward as his heir.

With the death of King Edward IV, leaving a child as his heir, another period of political unrest ensued and the War of the Roses resumed. Margaret was caught up in the crossfire of the struggle that ensued as well as contributing to the instability by fighting to put her own son on the throne. King Edward’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester had Edward’s children declared illegitimate, put aside young King Edward V and Parliament declared the Duke King. He was crowned King as Richard III. King Edward V and his young brother Richard, Duke of York were held in the Tower of London and after some time had passed they disappeared.

The new King was not sure of Margaret’s husband’s loyalty and for a short time had him imprisoned. But Stanley declared his support for Richard and was released, keeping all of his offices. Lord Stanley and Margaret played a role in the coronation of King Richard III and his wife Anne Neville. Margaret was magnificently dressed and carried the train of the new Queen. She also sat to the left of the Queen during the ceremony and sat near the Queen at the banquet afterwards.

There is some scant evidence that Margaret was already working on a plan to bring her son back to England at the very least; and wanted to have him named as the heir to the House of Lancaster and eventually made King at most. Margaret was not alone in working to oppose the new King. There is not much detail about these plans but when some men were discovered plotting against the King, they were caught and executed.

Margaret solicited the help of her nephew the Duke of Buckingham and of Edward IV’s Queen Elizabeth Woodville in her scheme. Part of the plot was the marriage of Margaret’s son to the former Queen’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York. She sent word to Henry in Brittany and he began preparations to return to England with troops.

King Richard was apprised of the rebellion and took his army to fight against Buckingham. There never was a battle due to bad weather but Buckingham was caught and executed. Margaret was attainted for treason by Parliament but because her husband remained loyal to Richard, the death sentence for treason was commuted to life in prison and her goods and lands were confiscated. Margaret’s imprisonment was served in the home of her husband. Lord Stanley gave Margaret quite a bit of freedom, allowing her to keep in contact with her son.

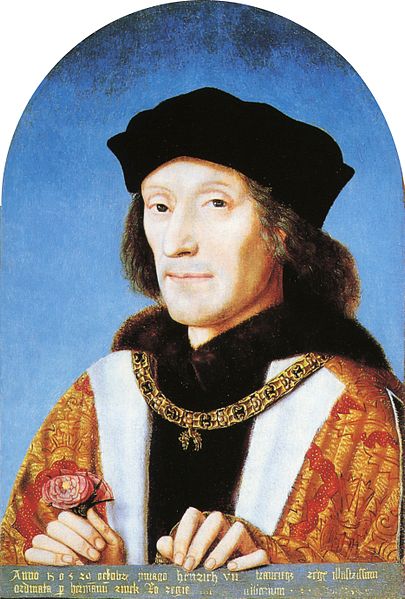

Margaret Beaufort’s son, King Henry VII (Image in public domain)

Over the next eighteen months, Margaret worked to get her son on the throne. Henry, in France, gathered supporters and troops and in the summer of 1485, he landed in England and engaged the forces of King Richard III at Bosworth Field. King Richard fought bravely but died on the battlefield and Margaret’s son Henry was now King as Henry VII. He couldn’t have done it without his mother’s help.

Margaret was immediately released from her imprisonment and traveled south for a reunion with her son in London after fourteen years. Henry gave his step-father the title of the Earl of Derby and Margaret was now known as the Countess of Richmond and Derby and “the King’s mother”. She witnessed Henry’s coronation on October 30, 1485 and his marriage to Elizabeth of York on January 18, 1486.

Margaret had a special place in her son’s government from the first day, providing him with trusted political advice. He entrusted her with many offices, titles, ceremonies and special commissions. She managed to legally and spiritually obtain independence from her husband so she owned everything in her own right. Henry gave her a home at Coldharbour near London and she made this her main home there along with another residence in the country called Collyweston. She basically acted as Queen, overshadowing her daughter-in-law.

In her later years Margaret made significant religious, educational and literary contributions. She became a patron and benefactor of two colleges at Cambridge University. She commissioned William Caxton to print a French romance book. She translated several devotional works from French into English and had them printed. Her personal chapel became an important center for the composition of polyphonic music.

Tomb of Margaret Beaufort in Westminster Abbey (Image in public domain)

Margaret’s beloved son King Henry VII died in April of 1509. Margaret lived long enough to see her grandson King Henry VIII marry Catherine of Aragon and witnessed their coronation on June 24th. Perhaps all the celebrations were too much for her as her health was failing. She died five days later at Westminster at the age of sixty-six. Her confessor, John Fisher, gave a eulogy describing her life about a month later. The Wheel of Fortune had finally stopped turning for Margaret.

Further Reading: “Margaret Beaufort: Mother of the Tudor Dynasty” by Elizabeth Norton, section on Margaret Beaufort from “The Women of the Cousins’ War: The Duchess, the Queen, and the King’s Mother” by Michael Jones, “Blood Sisters: The Hidden Lives of the Women Behind the Wars of the Roses” by Sarah Gristwood, entry on Margaret Beaufort in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography by M. Jones and M. Underwood