CHAPTER 2

http://www.wwnorton.com/college/polisci/essentials-of-international-relations5/ch/02/summary.aspx

Chapter Summary

I. INTRODUCTION

- The purpose of this historical overview is to trace important trends over time—the emergence of the state and the notion of sovereignty, the development of the international state system, and the changes in the distribution of power among states

- Contemporary international relations, in both theory and practice, is rooted in the European experience, for better or worse.

II. THE PRE-WESTPHALIAN WORLD

- Many international relations theorists date the contemporary system from 1648, the year of the Treaty of Westphalia, ending the Thirty Years War. This treaty marks the end of rule by religious authority in Europe. The Greek city-state system, the Roman Empire, and the Middle Ages are each key developments leading to the Westphalian order

- The Middle Ages: Centralization and Decentralization

- When the Roman empire disintegrated in the fifth century A.D., power and authority became decentralized in Europe.

- By 1000 A.D. three civilizations had emerged from the rubble of Rome:

- Arabic civilization: under the religious and political domination of the Islamic caliphate, advanced mathematical and technical accomplishments made it a potent force.

- Byzantine Empire: located near the core of the old Roman Empire in Constantinople and united by Christianity.

- The rest of Europe, where languages and cultures proliferated, and the networks of communication developed by the Romans were beginning to disintegrate.

- Much of Western Europe reverted to feudal principalities, controlled by lords and tied to fiefdoms that had the authority to raise taxes and exert legal authority. Feudalism was the response to the prevailing disorder

- The preeminent institution in the medieval period was the church; virtually all other institutions were local in origin and practice.

- Carolus Magnus, or Charlemagne, the leader of the Franks (in what is today France), challenged the church’s monopoly on power in the late eighth century.

- Similar trends of centralization and decentralization, political integration and disintegration, were also occurring in Ghana, Mali, Latin America, and Japan.

- The Late Middle Ages: Developing Transnational Networks in Europe and Beyond

- After 1000 A.D. secular trends began to undermine both the decentralization of feudalism and the universalization of Christianity in Europe. Commercial activity expanded into larger geographic areas. All forms of communication improved and new technologies made daily life easier.

- Economic and technological changes led to fundamental changes in social relations.

- A transnational business community emerged, whose interests and livelihoods extended beyond its immediate locale

- Writers and other individuals rediscovered classical literature and history, finding intellectual sustenance in Greek and Roman thought

- Niccolò Machiavelli, in The Prince, elucidated the qualities that a leader needs to maintain the strength and security of the state. Realizing that the dream of unity in Christianity was unattainable, Machiavelli called on leaders to articulate their own political interests. Leaders must act in the state’s interest, answerable to no moral rules.

- In the 1500s and 1600s, as European explorers and even settlers moved into the New World, the old Europe remained in flux. Feudalism was being replaced by an increasingly centralized monarchy.

- The masses, angered by taxes imposed by the newly emerging states, rebelled and rioted.

III. THE EMERGENCE OF THE WESTPHALIAN SYSTEM

- The formulation of sovereignty was one of the most important intellectual developments leading to the Westphalian revolution.

- Much of the development of sovereignty is found in the writings of French philosopher Jean Bodin. To Bodin, sovereignty was the “absolute and perpetual power vested in a commonwealth.” Absolute sovereignty, according to Bodin, is not without limits. Leaders are limited by natural law, laws of God, the type of regime, and by covenants and treaties.

- The Thirty Years War (1618-48) devastated Europe. But the treaty that ended the conflict, the Treaty of Westphalia, had a profound impact on the practice of international relations in three ways:

- It embraced the notion of sovereignty—that the sovereign enjoyed exclusive rights within a given territory. It also established that states could determine their own domestic policies in their own geographic space.

- Leaders sought to establish their own permanent national militaries. The state thus became more powerful since the state had to collect taxes to pay for these militaries and the leaders assumed absolute control over the troops.

- It established a core group of states that dominated the world until the beginning of the nineteenth century: Austria, Russia, England, France, and the United Provinces of the Netherlands and Belgium.

- The most important theorist at the time was Scottish economist Adam Smith. In An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that the notion of a market should apply to all social orders

- Individuals should be permitted to pursue their own interests and will act rationally to maximize his or her own interests

- With groups of individuals pursuing self-interests, economic efficiency is enhanced as well as the wealth of the state and that of the international system. This theory has had a profound effect on states’ economic policies.

IV. EUROPE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

- The American Revolution (1776) and the French Revolution (1789) were the products of Enlightenment thinking as well as social contract theorists.

- The Aftermath of Revolution: Core Principles

- Legitimacy: absolutist rule is subject to limits and imposed by man. In Two Treatises on Government, John Locke attacked absolute power and the divine right of kings. Locke’s main argument is that political power ultimately rests with the people rather than with the leader or the monarch.

- Nationalism: the masses identify with their common past, their language, customs, and practices. Individuals who share such characteristics are motivated to participate actively in the political process as a group.

- The Napoleonic Wars

- The political impact of these twin principles was far from benign in Europe. The nineteenth century opened with war in Europe on an unprecedented scale.

- Technological change allowed larger armies.

- The political impact of these twin principles was far from benign in Europe. The nineteenth century opened with war in Europe on an unprecedented scale.

- French weakness and its status as a revolutionary power made it ripe for intervention and the stamping out of the idea of popular consent

- The same nationalist fervor that brought about the success of Napoleon Bonaparte also led to his downfall.

- In Spain and Russia, nationalist guerillas fought against French invaders.

- Napoleon’s invasion of Russia ended in disaster, leading to French defeat at Waterloo three years later.

- Peace at the Core of the European System

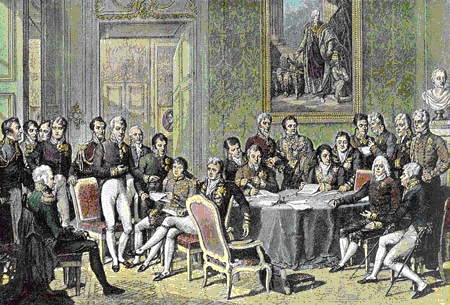

- Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and the establishment of peace by the Congress of Vienna, the Concert of Europe—Austria, Britain, France, Prussia, and Russia—ushered in a period of relative peace.

- The fact that general peace prevailed during this time is surprising, since major economic, technological, and political changes were radically altering the landscape.

- At least three factors explain the peace:

- European elites were united in their fear of revolution from the masses. Elites envisioned grand alliances that would bring European leaders together to fight revolution from below. Leaders ensured that mass revolutions did not love from state to state.

- Two of the major issues confronting the core European states were internal ones: the unifications of Germany and Italy. Although the unification of both was finally solidified, through small local wars, a general war was averted since Germany and Italy were preoccupied with territorial unification.

- Imperialism and colonialism

- Imperialism and Colonialism in the European System before 1870

- The discovery of the “New” World by Europeans in 1492 led to rapidly expanding communication between the Americas and Europe.

- Explorers sought discovery, riches, and personal glory.

- Clerics sought to convert the “savages” to Christianity

- European powers sought to annex distant territories. The term imperialism came to mean the annexation of distant territory, usually by force, and its inhabitants into an empire.

- Colonialism, which often followed imperialism, refers to the settling for people from the home country among indigenous peoples whose territories have been annexed.

- This process also led to the establishment of a “European” identity.

- European, Christian, civilized, and white were contrasted with the “other” peoples of the world.

- The industrial revolution provided the European states with the military and economic capacity to engage in territorial expansion.

- During the Congress of Berlin (1885), the major powers divided up Africa.

- Only Japan and Siam were not under European control in Asia.

- The struggle for economic power led to the heedless exploitation of the colonial areas, particularly Africa and Asia.

- As the nineteenth century drew to a close the control of the colonial system was being challenged with increasing frequency.

- During this period, much of the competition, rivalry, and tension traditionally marking relations among Europe’s states could be acted out far beyond Europe.

- By the end of the nineteenth century, the roll of political rivalry and economic competition had become destabilizing.

- The discovery of the “New” World by Europeans in 1492 led to rapidly expanding communication between the Americas and Europe.

- Balance of Power

- The period of peace in Europe was managed and preserved for so long because of the concept of balance of power.

- The balance of power emerged because the independent European states feared the emergence of any predominant state (hegemon) among them. Thus, they formed alliances to counteract any potentially more powerful faction

- The Breakdown: Solidification of Alliances

- The balance-of-power system weakened during the waning years of the nineteenth century. Whereas previous alliances had been fluid and flexible, now alliances had solidified.

- Two camps emerged: the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria, and Italy) in 1882 and the Dual Alliance (France and Russia) in 1893.

- In 1902 Britain broke from the “balancer” role by joining in a naval alliance with Japan to prevent a Russo-Japanese rapprochement in China. For the first time, a European state turned to an Asian one in order to thwart a European ally.

- Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese war in 1902 was a sign of the weakening of the balance-of-power system

- The end of the balance-of-power system came with World War I.

- Germany had not been satisfied with the solutions meted out at the Congress of Berlin. Being a “latecomer” to the core of European power, Germany did not receive the diplomatic recognition and status its leaders desired.

- With the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, Germany encouraged Austria to crush Serbia. Under the system of alliances, states honored their commitments to their allies, sinking the whole continent in warfare.

- Between 1914 and 1918, more than 8.5 million and 1.5 million civilians lost their lives.

V. THE INTERWAR YEARS AND WORLD WAR II

- The end of World War I saw critical changes in international relations:

- First, three European empires (Russia, Austro-Hungary, and the Ottoman) were strained and finally broke up during the war. With those empires went the conservative social order of Europe; in its place emerged a proliferation of nationalisms.

- Second, Germany emerged out of World War I an even more dissatisfied power. The Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended the war, made Germany pay the cost of the war through reparations. This dissatisfaction provided the climate for the emergence of Adolf Hitler, who was dedicated to right the “wrongs” imposed by the treaty.

- Third, enforcement of the Versailles Treaty was given to the ultimately unsuccessful League of Nations, the intergovernmental organization designed to prevent all future wars. The League did not have the political weight to carry out its task because the United States refused to join.

- Fourth, a vision of the post-World War I order had clearly been expounded, but it was a vision stillborn from the start. The world economy was in collapse and German fascism wreaked havoc on the plan for post-war peace.

- World War II

- World War II was started by Germany, Italy, and Japan.

- Japan had attacked China in a series of incidents beginning in 1931 eventually leading to war.

- Italy attacked Ethiopia in 1935, using yperite (a form of mustard gas banned by the Geneva Protocol).

- Nazi Germany was the biggest challenge, as it set to right what Hitler saw as the wrongs of the Treaty of Versailles.

- The power of fascism—German, Italian, and Japanese versions—led to the uneasy alliance between the communist Soviet Union and the liberal United States, Britain, and France. When World War II broke out, this alliance (the Allies) fought against the Axis powers in unison.

- The Allies at the end of the war were successful. Both the German Reich and imperial Japan lay in ruins at the end of the war.

- Two other features of World War II demand attention as well.

- The German invasion of Poland, the Baltic States, and the Soviet Union was followed by the organized murder of human beings, including Jews, Gypsies, communists, and Germans who showed signs of genetic defects.

- While Germany surrendered in May 1945, the war did not end until the surrender of Japan in August.

- In order to avoid a costly invasion, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- The new weapon, combined with the Soviet declaration of war against Japan led to the surrender of Japan to the Allies.

- The end of World War II resulted in a major redistribution of power and changed political borders.

- World War II was started by Germany, Italy, and Japan.

VI. THE COLD WAR

- Origins of the Cold War

- The most important outcome of World War II was the emergence of two superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—as the primary actors in the international system and the decline of Europe as the epicenter of international politics.

- The second outcome of the war was the recognition of fundamental incompatibilities between these two superpowers in both national interests and ideology.

- Russia used its newfound power to solidify its sphere of influence in the buffer states of Eastern Europe.

- U.S. interests lay in containing the Soviet Union. The United States put the notion of containment into action in the Truman Doctrine of 1947. After the Soviets blocked western transportation corridors to Berlin, containment became the fundamental doctrine of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War.

- The U.S. economic system was based on capitalism, which provided opportunities to individuals to pursue what was economically rational with little or no government interference.

- The Soviet state embraced Marxist ideology, which holds that under capitalism one class (the bourgeoisie) controls the ownership of production. The solution to the problem of class rule is revolution wherein the exploited proletariat takes control by using the state to seize the means of production. Thus, capitalism is replaced by socialism.

- Differences between the two superpowers were exacerbated by mutual misperceptions. The Marshall Plan and establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) were taken as a campaign to deprive the Soviet Union of its influence in Germany. Likewise, the Berlin Blockade was interpreted by the West as a hostile offensive action.

- The third outcome of the end of World War II was the beginning of the end of the colonial system. European colonialists. Beginning with Britain’s granting of independence to India in 1947, Indochina and African states became independent in the 1950s and 1960s

- The fourth outcome was the realization that the differences between the two superpowers would be played out indirectly, on third-party stages, rather than through direct confrontation between the two protagonists. The superpowers vied for influence in these states as a way to project power.

- The Cold War as a Series of Confrontations

- The Cold War itself (1945-89) can be characterized as forty-five years of high-level tension and competition between the superpowers but with no direct military conflict.

- More often than not, the allies of each became involved, so the confrontations comprised two blocs of states: those in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Western Europe and the United States, and the Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe.

- One of those high-level, direct confrontations between the superpowers took place in Germany.

- Germany had been divided after World War II into zones of occupation. In the 1949 Berlin blockade, the Soviet Union blocked land access to Berlin, prompting the United States to airlift supplies for a year.

- In 1949, the separate states of West and East Germany were declared.

- East Germany erected the Berlin Wall in 1961 in order to stem the tide of East Germans trying to leave the troubled state.

- The Cold War in Asia and Latin America

- China, Indochina, and especially Korea became symbols of the Cold War in Asia.

- By 1949 the Kuomintang was defeated in China and its leaders fled to the island of Formosa (not Taiwan).

- In French Indochina communist forces fought against the French colonial forces leading to the eventual French defeat in 1954.

- In 1950 North Korea attempted to reunify the Korean peninsula under communist rule, launching at attack against the South.

- U.S. forces, fighting under the auspices of the United Nations, counterattacked and nearly defeated North Korea.

- As UN troops approached the Chinese border, the Chinese attacked, driving the UN forces South and leading to an eventual three-year stalemate ending in a armistice in 1953.

- The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was another direct confrontation in yet another part of the world. The Soviet Union’s installation of missiles in Cuba was viewed by the United States as a direct threat to its territory.

- In Vietnam, the Cold War played out in an extended civil war, in which communist North Vietnam were pitted against South Vietnam.

- U.S. policy makers argued that communist influence must be stopped before it spread like a chain of falling dominoes throughout the rest of Southeast Asia (hence the term domino theory).

- China, Indochina, and especially Korea became symbols of the Cold War in Asia.

- The “Cold” in “Cold War”

- It was not always the case that when once of the superpowers acted the other side responded.

- When the Soviet Union invaded Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, the United States verbally condemned such actions but the actions themselves went unchecked.

- The Soviets kept quiet when the United States invaded Granada in 1983 and Panama in 1989.

- The Middle East was a region of vital importance to both the United States and Soviet Union, and thus the region served as a proxy for many of the events of the Cold War.

- Following the establishment of Israel in 1948, the region was the scene of a superpower confrontation by proxy: between a U.S.-supported Israel and the Soviet-backed Arab states of Syria, Iraq, and Egypt. Proxy “hot” wars, such as the Six-Day War in 1967, and the Yom Kippur War in 1973 were fought.

- Confrontation through proxy also occurred in parts of the world of less strategic importance, such as the Congo, Angola, and the Horn of Africa.

- The Cold War was also fought and moderated in words, at summits (meetings between the leaders) and in treaties.

- Some of these summits were successful, such as the 1967 Glassboro Summit that began the loosening of tensions known as détente.

- Treaties placed self-imposed limitations on nuclear arms.

- It was not always the case that when once of the superpowers acted the other side responded.

- The Cold War as a Long Peace

- John Lewis Gaddis has referred to the Cold War as a “long peace” to dramatize the absence of war between the great powers. Why?

- Nuclear deterrence: Once both the United States and Soviet Union had acquired nuclear weapons, neither was willing to use them.

- Division of power: the parity of power led to stability in the international system

- The stability imposed by the hegemonic economic power of the United States: being in a superior economic position for much of the Cold War, the United States willingly paid the price of maintaining stability throughout the world.

- Economic liberalism: the liberal economic order solidified and became a dominant factor in international relations. Politics became transnational under liberalism—based on interests and coalitions across state boundaries—and thus great powers became obsolete.

- The long peace was predetermined: it is just one phase in a long historical cycle of peace and war.

- John Lewis Gaddis has referred to the Cold War as a “long peace” to dramatize the absence of war between the great powers. Why?

VII. THE POST-COLD WAR ERA

- The fall of the Berlin Wall symbolized the end of the Cold War, but actually its end was gradual. Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev had set in motions two domestic processes—glasnost (political openness) and perestroika (economic restructuring)—as early as the mid-1980s.

- Gorbachev’s domestic reforms also led to changes in the orientation of Soviet foreign policy. He suggested that members of the UN Security Council become “guarantors of regional security.”

- The first post-Cold War test of the new so-called new world order came in response to Iraq’s invasion and annexation of Kuwait in 1990.

- A few have labeled the end of the Cold War era the age of globalization. This era appears to be marked by U.S. primacy in international affairs to a degree not even matched by the Romans.

- However, U.S. primacy is still not able to prevent ethnic conflict, civil wars, and human rights abuses from occurring.

- The 1990s was a decade marked by dual realities (and sometimes converged and diverged), the first being U.S. primacy and the second being civil and ethnic strife.

- Yugoslavia’s violent disintegration played itself over the entire decade despite Western attempts to resolve the conflict peacefully.

- At the same time, the world witnessed ethnic tension and violence as genocide in Rwanda and Burundi went unchallenged by the international community.

- On September 11, 2001, the world witnessed deadly, and economically destructive terrorist attacks against two important cities in the United States. These attacks set into motion a U.S.-led global war on terrorism.

- The United States fought a war in Afghanistan to oust the Taliban regime, which was providing safe haven to Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda organization and a base from which it freely planned and carried out a global terror campaign against the United States.

- Following the initially successful war in Afghanistan, the United States, convinced that Iraq maintained weapons of mass destruction and supported terrorist organizations, attempted to build support in the United Nations for authorization to remove Saddam Hussein from power. When the United Nations failed to back the U.S. request, the United State built its own coalition and overthrew the Iraqi government. The fight continues today.

- Despite its primacy, the United States does not feel it is secure from attack. The issue of whether U.S. power will be balanced by an emerging power is also far from resolved.

VIII. IN SUM: LEARNING FROM HISTORY

- Whether the world develops into a multipolar, unipolar, or bipolar system depends in part on by looking to the trends of the past and how they influence contemporary thinking. Or is the entire concept of polarity an anachronism?

No comments:

Post a Comment