Graham Goodlad examines the controverisal reputation of Napoleon Bonaparte as a military commander.

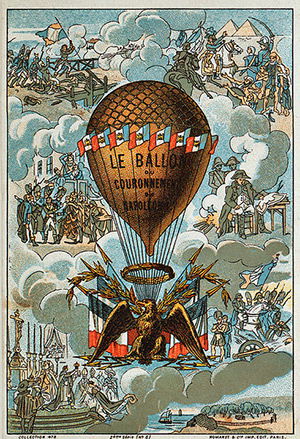

"Napoleon's coronation balloon". Collecting card with vignettes of Napoleon's military victories.

"Napoleon's coronation balloon". Collecting card with vignettes of Napoleon's military victories.

Command and Control

It is not hard to see why Napoleon has been numbered among the great commanders of history. A Napoleonic scholar, Gunther Rothenberg, has calculated that he personally commanded 34 battles between 1792 and 1815, of which he lost only six. For a period of ten years he dominated Europe, heading an empire that stretched from the Channel coast to the borders of Russia. The foremost military theorist of the age of Napoleon, Carl von Clausewitz, hailed him as ‘the god of War’, whilst in slightly more restrained fashion the modern historian Martin Van Creveld has described him as ‘the most competent human being who ever lived’. What were the distinctive qualities of leadership that brought such accolades?

Napoleon was essentially a practical individual, who did not commit his thoughts on strategy to paper in a systematic manner. His occasional observations on the subject simply underline his essential pragmatism: he declared that ‘there are no precise or definite rules’ and ‘the art of war is simple, everything is a matter of execution’. Most historians would, however, agree that at the core of his philosophy was a belief in offensive action, aimed at a decisive clash with the enemy’s forces. Napoleon’s primary objective was the destruction of the opposing army rather than the seizure of territory or the capital city. This was demonstrated in the campaign of 1805, when he set out from France to crush the Austrian forces. In October, barely seven weeks after they left the camp at Boulogne, French forces surrounded General Mack’s army at Ulm in southern Germany, forcing its surrender almost without bloodshed. Five weeks later, after marching a further 500 miles to the east, the French defeated a combined Austro-Russian army at Austerlitz. These victories effectively gave control of central Europe to France.

Rapid movement and the concentration of superior force were to a great extent dictated by practicalities. The French Revolution had seen a significant expansion in the size of armies – a trend which continued throughout the Napoleonic Wars. In 1805 Napoleon’sGrande Armée numbered some 210,000 men; the French army that invaded Russia seven years later had practically trebled in size. Although the agricultural revolution of the eighteenth century created a food surplus, enabling armies to live off the land more easily than in previous generations, it was still necessary for them to continue moving to new areas in search of subsistence. It should be remembered that armies of this period depended heavily on horses for transport and that the daily food consumption of a horse was ten times that of a soldier. These considerations favoured a highly mobile, focused and aggressive style of warfare. It is noteworthy that in the two theatres of war where Napoleon met with catastrophic defeat – Spain and Russia – agricultural development was limited, forcing the French to rely on cumbersome supply trains. In the case of Russia in 1812, poor roads, combined with the enemy’s willingness to deprive the French of resources through a deliberate ‘scorched earth’ policy, rendered the invasion unsustainable. Napoleon failed in Russia because he was unable to draw the enemy’s principal force into the decisive battle that he always favoured.

Master of the Battlefield

Napoleon’s was an intensely personal and highly centralised style of waging war. Although his imperial headquarters evolved into a complex staff apparatus, its role was essentially the implementation of Napoleon’s instructions. Historians have frequently remarked on his impressive powers of work and his excellent memory, which enabled him to maintain a close oversight of numerous complex troop movements. His ability to direct and co-ordinate his forces was the more impressive in an age when methods of communication remained rudimentary – a generation before the invention of the electric telegraph and two generations before the radio.

Napoleon’s characteristic mode of operation was to have his army, divided into a number of self-contained corps consisting of infantry, cavalry and artillery, travel along separate but parallel routes. A cavalry screen ahead of the advancing army would gather intelligence whilst also confusing the enemy as to Napoleon’s intentions. The formation would close up in a loose quadrilateral, the bataillon carré, once the main enemy force had been located. The first corps to make contact would then seek to pin the enemy whilst the main French force would attack his rear, thereby threatening his line of communications – the so-called manoeuvre sur les derrières. The enemy would therefore face an unenviable choice between surrender and giving battle without a secure line of retreat. The Austrian capitulation at Ulm is a classic example of this technique in action. Another way in which Napoleon sought to isolate his opponents from their base camps was to use overwhelming force at one point in the enemy lines, punching a hole and then completing the encirclement from the rear.

An alternative method, used against an enemy who possessed superior numbers, was that of the ‘central position’. The object was to divide the opposing forces into several parts and to win local superiority over each in turn. Whilst a portion of Napoleon’s forces engaged one part of the enemy army, he would turn his main body against the other part and defeat it. The main force would then join the pinning force to finish off the second section of the opposing army. An early example of Napoleon’s use of this method was his response to the Austrians’ attempts to relieve the siege of Mantua, during his 1796 campaign in Italy. He dealt separately with the two Austrian columns that were converging on the city.

Mastery of grand tactics was not in itself sufficient to secure victory. It should be noted that the methods employed by Napoleon had been available to other generals of the French Revolutionary era. What distinguished Napoleon was his ability to grasp the essentials of a situation and to integrate all the elements of his response with speed and clarity. In this he was assisted by his effective intelligence gathering system, which informed him of enemy movements, and by his emphasis on the production of accurate and detailed maps. Added to these technical skills was a unique capacity to inspire and motivate his troops. This was achieved partly through staying close to them, as his nickname, le petit caporal (‘the little corporal’) testifies. The name derived from his performance at the Battle of Lodi in Italy in May 1796, when Napoleon drew on his own training as an artilleryman to site some of the French guns in person. Napoleon’s personal charisma communicated itself in the addresses that he directed to his troops. Before the Battle of the Pyramids in July 1798, for example, he dramatised the event in memorable fashion: ‘Soldiers, consider that from the summit of these pyramids, forty centuries look down upon you.’ The issuing of individual rewards and recognitions of collective achievement consolidated his hold on his men’s affections. It meant that he was able to make exceptional demands on them. The rapid reformation of Napoleon’s 200,000 strong Grande Armée in the spring of 1815, after he returned to France from exile on the island of Elba, is a tribute to his ability to project his personality.

Planning and Improvising

In any analysis of Napoleon’s skills as a commander we need to be aware of the extent to which he reacted intelligently to circumstances – sometimes with a certain amount of luck – rather than following through a predetermined plan of action. He himself stated, during his final period of exile, that the mark of a great general is the ‘courage to improvise’. Prior to the encirclement at Ulm, for example, Napoleon first drove his army beyond the enemy’s main position, across the River Danube to the south bank, before he discovered that the Austrians were actually behind him, on the north bank. He then ordered much of his army back across the Danube in order to trap the Austrians.

Nor should we imagine that Napoleon invariably secured military victory without the assistance of able subordinates. In the October 1806 Jena-Auerstädt campaign against Prussia, the emperor initially miscalculated but the day was saved by the skill of Marshal Davout. At the outset Napoleon characteristically took the offensive, seeking to cut the Prussian forces off from their capital, Berlin, and to crush them before their Russian allies could intervene. He mistakenly believed that the Prussians whom he encountered at Jena, and defeated with overwhelming numbers, constituted the main body of the enemy. The truth was that Davout, who had been dispatched to the north, had in fact met the bulk of the Prussian army, led by the Duke of Brunswick, at Auerstädt. It was a tribute to Davout that he managed to overcome the much larger Prussian force, bringing his three divisions into line to check the enemy advance. He then launched a ferocious counter-attack, causing the Prussian forces to break and flee towards Jena where the other wing of their army was disintegrating.

It is also important to be aware of the extent to which Napoleon owed his success to the mistakes and failings of his adversaries. At Austerlitz, for example, the Russian Tsar Alexander I accepted battle on terrain of Napoleon’s choosing. He ill-advisedly took at face value a tactical withdrawal by the French forces, in the process overruling his more cautious but experienced general, Kutuzov. Similarly the outcome of the Jena-Auerstädt campaign can be attributed in part to weaknesses in the Prussian high command. The Duke of Brunswick was a poor choice as commander- in-chief and there was no unity among the senior figures in the recently created general staff. At Auerstädt the Prussians failed to bring their numerically significant reserve into play, which might have turned the tide if used appropriately. Napoleon’s enemies certainly presented him with opportunities that he was able to exploit.

The Author of his Own Downfall?

Some historians have detected a falling off in Napoleon’s abilities as a general from about 1809. He himself privately reflected in 1805 that ‘I will be good for six years more; after that even I must cry halt.’ Before that time had elapsed, contemporaries noted that his reactions were deteriorating and his health was often poor. A corresponding decline in the quality of his army also began to have an effect. Yet the logic of conquest drove him to embark on more or less continuous warfare. A powerful case can be made for the claim that Napoleon was ultimately responsible for his own downfall.

In the early years of the empire, Napoleon had profited from advances in tactics and organisation introduced before he attained high command. The ordre mixte, for example, which combined the advantages of shock and fire by linking formations in column with others in line, was established as French practice before his time. Napoleon also benefited from the experience gained by French troops in the fighting of the Revolutionary Wars. The men he led were far more professional and battle-hardened than those who had first been called upon to resist the enemies of the Revolution in 1792. The introduction of conscription moreover made available a much larger reservoir of troops. Warfare on a Napoleonic scale required a commitment of large numbers to the battlefield and a willingness to accept a high level of casualties. It has been estimated that by 1809 the number of dead, wounded and otherwise incapacitated French troops equalled the 210,000 who had made up the grande armée originally assembled four years earlier.

In order to fill the gaps the empire was obliged to recruit less skilled men, so that infantry tactics were at once less sophisticated and more wasteful in terms of lives. In battle troops were used increasingly to batter a way through the enemy lines, whilst artillery were used in greater quantities. The historian of battle tactics, Brent Nosworthy, dates this change from the Battle of Wagram (July 1809), where Napoleon gained success at the cost of heavy casualties. At the same time, growing demands for manpower in satellite states, such as the Kingdom of Italy, placed a strain on the acceptance of French rule by local populations. No more than half of the 600,000 troops gathered for the invasion of Russia in June 1812 were French. The inferior quality and motivation of these reluctant auxiliaries contributed to the weakening of Napoleon’s power. In addition, the heavy losses sustained in the Russian campaign – fewer than one in ten returned to France – were extremely difficult to make good. The situation was exacerbated by the continuing loss of manpower as he strove unsuccessfully to reduce Spain and Portugal to obedience in the long-running Peninsular War of 1803-13. Once Austria, Prussia and Russia had combined their forces in central Europe, Napoleon faced daunting odds. His defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, in which 200,000 French faced 342,000 coalition troops – an engagement which paved the way for the invasion of France the following year – was the unavoidable consequence.

Napoleon’s fall was not, however, caused solely by purely military factors. At a deeper level, the nature of the empire and the personality of its leader were to blame. Napoleon’s programme of conquest meant that he could never rest from conflict for long. His accommodations with other powers, such as the Treaty of Tilsit with Russia in July 1807, or his marriage alliance with the Austrian royal family three years later, were pragmatic arrangements, devised purely to serve French interests, rather than genuine harbingers of peace. His alliance partners never trusted him and the demands that he placed upon them bred a slowburning desire for revenge. An additional complication was Napoleon’s inability to defeat Britain, whose naval supremacy was demonstrated at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805. This led him to introduce the so-called ‘Continental system’, an attempt to cut mainland European states off from trade with Britain. The economic damage that was inflicted on Napoleon’s unwilling satellites was a major source of grievance. Portugal’s refusal to co-operate with the trade embargo drew Napoleon into the Peninsular War. Tsar Alexander I’s decision to end his participation in it was an important cause of the rupture between France and Russia. Napoleon invaded Russia in an ill-fated attempt to compel its return to the Continental system and to reassert French dominance of Europe.

The reality of Napoleonic rule was that its extension generated increasingly powerful resistance, ultimately threatening its very survival. The emperor’s refusal to acknowledge anything except French self-interest eventually drove the other powers to reorganise and to coalesce for long enough to ensure his defeat. His inability to compromise forced them to conclude that there was no prospect of a lasting settlement and that therefore renewed war was the only course of action.

The Uniqueness of Napoleon

Later generals looked back on Napoleon with admiration, in spite of his eventual defeat, and sought to emulate his aggressive style of warfare. The Prussian commander Helmuth von Moltke, for example, who won three wars against Denmark, Austria and France in 1864- 71, could certainly be described as ‘Napoleonic’ in his generalship. The wars of German unification were won through a combination of careful planning, rapid penetration of the enemy’s defences and concentration of force, suitably updated to take account of developments in firepower and railway communications. Moltke also shared Napoleon’s flexibility, famously stating that ‘no battle plan survives contact with the enemy’.

Never again, however, would a single individual combine, as Napoleon did, the political leadership of a major state with the professional command of armies in the field. The growing complexity of warfare in the nineteenth century – and still more in the twentieth – meant that the tasks he handled in person had increasingly to be delegated to trained military staffs. Even in the closing years of Napoleon’s military career, it was not really feasible for one commander, however talented, to exercise direct personal control over battlefields on which hundreds of thousands of troops were now engaged. In a real sense his career and achievements were unrepeatable.

Timeline

- 1796-97 Napoleon’s first command as general of French forces in Italy

- 1798 Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt

- 1804 Napoleon crowned French emperor 1805 Austrian defeat at Ulm; Austro- Russian forces defeated at Austerlitz

- 1806 Prussia defeated at Jena-Auerstädt

- 1807 Russia defeated at Friedland; Tsar Alexander I signs Treaty of Tilsit

- 1808-13 Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal

- 1808-14 Revival of Austrian opposition; ends in defeat at Battle of Wagram

- 1812 Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia

- 1813 Napoleon defeated at Leipzig by combined Austro-Russian- Prussian forces

- 1814 Napoleon forced to abdicate and exiled to Elba

- 1815 Napoleon returns to France; the ‘Hundred Days’ ends in defeat at Waterloo

Issues to Debate

- How far did Napoleon’s success as a general depend on the weaknesses and mistakes of his opponents?

- How justified is the claim that Napoleon ‘scrambled to victory’ rather than implementing a prepared plan of action?

- How far were flaws in Napoleon’s generalship to blame for his eventual downfall?

Further Reading

- David A Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Modern Warfare (Bloomsbury, 2007)

- David Chandler, Napoleon (Pen and Sword, 2001)

- Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military Campaigns (Rowman and Littlefield, 2006 edition)

- Charles Esdaile, Napoleon’s Wars (Allen Lane, 2007)

- Brent Nosworthy, Battle Tactics of Napoleon and his Enemies (Constable, 1995)

- Jonathon Riley, Napoleon as a general: command from the battlefield to grand strategy (Hambledon Continuum, 2007)

- Gunther Rothenberg, The Napoleonic Wars (Cassell, 1999)

No comments:

Post a Comment